When We Played for 40 Million People (and Didn't Know It)

In 1986, Atlantic Records sent Valerie and me on a promotional tour of Europe. We were jet-lagged, shell-shocked by sudden fame, and completely unprepared for what we would find across the pond. We appeared on over a dozen radio and TV shows in England, France, and Italy, including a little BBC thing called…TOP OF THE POPS.

Welcome to the pre-Internet era of rock stardom, where you could conquer Europe and have no clue you were doing it.

It was the summer of 1986, and the Nu Shooz song ‘I Can’t Wait’ was a Top-5 hit all over the world.

Our label, Atlantic Records, sent us over to Europe to do press and TV appearances; not the whole band, just Valerie and me. We were too busy to notice that the label wasn’t interested in the band, and was marketing us as a Husband and Wife ‘Synth-Pop’ Duo from Portland, Oregon.

We had an eight-hour hop over the North Pole. A car picked us up at Heathrow. On the way into town, our song came on the radio. Pretty cool!

So here we are in London.

It was the Pre-Internet era, what we call ‘the Horse and Buggy days.’ There was no way to do research into which media outlets we were slotted to appear on. We didn’t know if we were going to be on the British version of Dick Clark or Howdy Doody. Nowadays it’s so easy. Does the interviewer have an audience of ten thousand, or a million…or twelve? Is the show we’re going on a local morning show, or syndicated around the world?

Besides being jet-lagged and shell-shocked by our sudden rise to fame, we were clueless about the music business…I mean the POP music business.

We were scheduled to be on a show called Top of the Pops on the BBC. Never heard of it.

John’s Journal from 1986

But first, we were ushered into a recording studio, where a room full of musicians was re-recording our song! What? The label rep took us aside and quietly explained that the British Musician’s Union requires that British musicians have to be hired to play any music that will appear on TV. I remember the guitar player didn’t have the part quite right, but the horns and the backup singers were better than the record!

I asked the label guy, “Do we have to use this version?” “Oh no,” he laughed. Nudge nudge wink wink. “This is all for appearances. Don’t worry.”

Before our appearance on Top of the Pops, we flew up to Manchester to be on a cute little ‘jukebox’ show, a sort of Dick Clark/American Bandstand in miniature. Fine Young Cannibals were on the show too. The audience was mostly middle-school kids. (Thirty or forty years later, someone sent us a clip of that show which was re-broadcast in Germany!)

Our driver for the British leg of the trip was a portly gentleman named Bil. [One ‘L.’] He took a liking to us right away and vice versa.

“You folks aren’t like the usual Rock Stars,” he said. “You’re real people.” He went above and beyond the call of duty and showed us around London, a city he clearly loved. I remember he showed us some Medieval doorways on London Bridge, barely five feet high. “People were much shorter then.”

John and our driver, Bill, on the London Bridge.

He took us to the oldest Toy Store in England, established in the late 1700’s. He bought me a little box of toy soldiers- I still have them- dressed like Hussars from the Crimean War. He introduced us to his wife, and we all had fish and chips at his local pub. All in all a perfect London experience; one we never could have had as mere tourists.

I think we did a couple of morning shows, and then it was onto Top of the Pops. I was used to hiding out in the corner of our nine-piece band, so now I’m feeling naked. It’s just Val and me out there doing these silly dance steps, miming our song. But what I mostly remember is I made one of the worst fashion choices of my career, a stupid, ill-fitting beret!

It was all a great big swirl.

A different driver picked us up to go to the airport, and we never saw BIL again; never got to thank him for being the best part of our trip.

Then it was on to Paris.

The French label put us up in a palatial suite at the Hotel Nikko overlooking the Seine.

I think we did about ten TV shows while we were there, mostly morning shows. I don’t know how effective it was since we didn’t speak French. The last thing we did was a TV show called ‘La vie du Famille.’ (Family Life) It was a kind of Ed Sullivan/Hollywood Palace kind of revue…you know, pop singers but also jugglers. I can still hear the theme song in my head forty years later:

La vie du famille

C’est important

Also on that show were Vince Clarke of Erasure, and the ‘Soul Makosa’ man, Manu Dibango.

Backstage, taking an old-fashioned 80s selfie.

Next, it was on to Italy, where we did some radio.

(They pronounced the name of our band like New Shoots.) We were scheduled to appear at an outdoor show in Sienna. It was part of a festival called the Pallio, sort of like the running of the bulls in Pamplona, but with horses. It had been going on for the last 500 years!

Sienna, Italy

Squads of Ghibbellines and Guelfs did that drill where they toss flags in the air. The food was better than in France, that’s for sure. And I was getting used to the Synth-Pop-Duo thing. To get out of doing dance steps, I refused to lip-sync guitar and hid behind a dead keyboard instead.

There was a Brit Punk band called Sigue Sigue Sputnik on the show, with their Statue-of-Liberty hair-dos. They were flipping off the audience. Well, I never dug the Punk thing.

Anyway, the point of this story is, in the Pre-Internet era, there was no way to look things up, to find out what we were getting into. As we learned much later, Top of the Pops was beamed all over Europe and in the 80s had an audience of FORTY MILLION PEOPLE!

If I had known, I would have insisted on bringing the band!

And maybe chosen a better hat.

Everything About The Making Of I Can't Wait

Did you know 'I Can't Wait' was originally much faster? When we slowed it down to 104 BPM in the studio, the band thought John was crazy! But that slower groove, combined with some engineering magic and creative percussion (including wine bottles!), helped create the sound y’all know and love.

The most frequently asked FAN QUESTIONS are about the making of “I Can’t Wait.” So, here’s an attempt to include every technical detail about how we made that song forty-one years ago. It’s amazing that we’re still talking about it almost half a century later!

The recording of “I Can’t Wait” perfectly captures that unique moment in music history when analog and digital technologies were colliding. Looking back, it’s amazing how we managed to create such a rich, layered sound with relatively simple equipment. Every decision - from the LINN drum machine to engineer Fritz’s compression techniques - helped shape what would become Nu Shooz’s signature hit.

Subject: I Can't Wait production

Message: Hello Valerie and John! I was listening to "I Can't Wait" today and would love to know how the song was produced. Equipment. Instruments. Etc... Has this information ever been shared in an interview somewhere that I can look up? Thanks for this wonderful classic. — Patrick

Hi Patrick!

Thanks for your letter. We get asked this question a lot, so I'm going to write down the definitive version of THE MAKING OF 'I CAN'T WAIT.'

EVERYTHING ABOUT THE MAKING OF NU SHOOZ 'I CAN'T WAIT' (That we can remember.)

It was the winter of 1983, a time almost unrecognizable now. TV still signed off at 2 a.m. Cable was just getting started. And none of the gear existed that we take for granted now. MIDI was new and prohibitively expensive. NU SHOOZ had a horn section but no keyboards.

Without MIDI or a multitrack, it was harder to write songs, to make them stand up and walk around by themselves. We were playing all the time, almost every weekend, and this created an insatiable need for new material. People would leave the band and you couldn't play this or that song anymore. The new guy would come in, and we'd have to teach him all the moldy oldies. There were songs I was so tired of that it hurt to play them. And in Portland, funk records were hard to find. So, I had to become a full-time songwriter. In the Brill Building days, writers like Carole King and Jerry Goffin made hit songs by putting in the hours—showing up every day.

I started writing songs in batches of ten. How it worked was, I'd number one to ten on a piece of paper and then slot in a bunch of tempos, like this:

Mid-tempo [meaning funk]

Mid-tempo

Fast

Mid-tempo

Slow

Fast... etc

Next, I would assign a Kick/Snare pattern to each number. When you're writing songs, specifically Funk songs, you become a connoisseur and collector of Kick/Snare patterns. Some of my personal favorites are Surf Beats for fast stuff, and anything by Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis for the FUNK.

I got a lot of Nu Shooz Kick/Snare patterns from the Grandmaster Flash album 'THE MESSAGE.'

I tried to finish two songs a week for Wednesday rehearsal. I.C.W. was one of the first songs to come out of this batch writing process.

As I said before, it was hard without any gear to make a song hang together in your head. My Mother-in-Law had this thing called an OMNICHORD. It looked sort of like a zither, but it was completely electronic. It had a little drum machine in it, you know, like those old 'Home Organ' beats: Swing, Waltz, Bossa Nova, etc. And there was one called ROCK BEAT 1.

I plugged the OMNICHORD into a cassette machine and recorded ROCK BEAT 1 at a bunch of different speeds. This worked for all the tempos mentioned above. This was a vast improvement. Before that, I was trying to make drum beats by banging on a kitchen table with dinner plates on it.

Then I begged our manager to rent a ¼" four-track machine from the local sound company. For the princely sum of $24 a month, they rented us a TEAC 3440. Great machine. [I still have it, by the way.] Right away, I filled a tape with my OMNICHORD beats, and just like that, I was in business. Writing songs was suddenly so much easier.

I.C.W. was written while sitting on a wooden stool next to the furnace in our basement rehearsal space. The bass line was composed on a 1965 Fender P-Bass [Black/Rosewood Fretboard/Tortoiseshell guard] belonging to our Soundman. The Bass was tuned to Drop-D. The chords were played on a cheap [but nice] nylon string guitar called a DISCOTECA SERRANO.

I mixed the demo to cassette, put it in my Walkman, and spent the next month or so walking around and around the block. The first chorus bit that I heard in my head was:

"I Can't Wait till FRIDAY NIGHT"

Eventually, that morphed into the call-and-response:

'Cause I Can't Wait

BABY

I CAN'T WAIT.

Phew!

So now that the chorus was "sitting still," the song needed verses.

My love— The first two words of a Lionel Richie song

Tell me what it's all about— A line from my Bone Pile

You've got something

That I can't live without— A vague come-on

Happiness— The first word in an Alan Toussaint song

Is so hard to find— My answer to his line

Etc., etc.

Back then, I was good at one-and-a-half verses.

Anyway…

We had a Wednesday rehearsal coming up, and I didn't have anything but this half-finished song. The band was actually loading their gear into the basement. Valerie was standing at the sink, and I was at the kitchen table. In ten minutes, I wrote the rest of the song. There! I shoved the paper at Valerie.

She said, "Good enough."

There was just enough time left to scribble up a horn chart.

So now it's 1984, and we're playing I.C.W. in the clubs. We called it a B-level dance song. People danced to it, but we played it way too fast, just to get it over with. Around that time, Rick, our manager, called.

"We need to record something. I need something to market."

He didn't like our first album, "Can't Turn It Off," and he was right. It didn't represent the band anymore. Rick had just inherited five grand from a deceased aunt, and he wanted to bankroll a Nu Shooz album.

He asked me, "Do you have any songs you like?"

"Well," I said, "the one that sounds the most real is 'I Can't Wait.'"

By real, I meant that it sounded the most like a real record. Valerie sounded great on it right away. [Her voice worked perfectly an octave above my songwriter croak.]

Rick booked us into Cascade Studio in Portland, Oregon. Sessions began in the summer of 1984. Before we went into the studio, I was pondering whether or not to use a drum machine. We used to make fun of the early ones. The ROLAND 808 only became popular with the advent of Hip-Hop. We tried cutting the song with a live drummer first, and that just didn't work. We had to have that machine kick/snare/clap…like ZAPP!

For a band that couldn't afford keyboards, a drum machine was out of the question.

Fortunately…

We knew a rich guy who didn't play but had a house full of all the best gear.

He owned a LINN LM-1.

The LINN LM-1 was Roger Linn's first commercially available drum machine. It was so much heavier sounding than an 808. It retailed for $5,000 [in '80s money!]

Next, we put on a bass.

Live bass didn't cut it, either. So we hired a bass player, Nate Philips, who owned a MINI-MOOG. He was one of the great Portland funk players, going back to the '70s band Pleasure. Nate dialed in the sound and played the part. I got my own MINI-MOOG not long after that, but I never could get close to the sound that he made.

The piano was a seven-foot Steinway.

The guitars were a cream-white [nicotine yellow] 1969 Fender Stratocaster and my number one fave 1967 Gibson 335 [battered black].

This is it — John’s 1967 Gibson ES335.

The horns are real, just trumpet and tenor doubled.

Our saxophone player, Dan Schauffler, had just bought a ROLAND JX-3P synth. It had eight preset sounds, and I'm pretty sure we used them all. A good example is the chime in the intro, which was kind of a take-off on "Tubular Bells" by Mike Oldfield, and the legato synth string line that follows. The JX-3P was one of the first commercially available MIDI synths. Everything was new back then.

The Roland JX-3P in all it’s magnificence.

Cascade Studio had a two-inch 16-track machine, which was and is kind of rare, then and now.

It was a real stroke of luck for two reasons. First of all, the tracks are wider than a 2" 24-track, and they actually have a fatter sound. And second, we didn't have those eight extra tracks to clutter up the song.

Before we had anything on tape, I had an epiphany and realized that it would be so much funkier if we slowed it down. I tramped around the studio parking lot, singing the bassline, feeling for where the funky place was. Then I ran back into the control room. We slowed it down to 104 bpm from however the hell fast we were used to playing it.

The band thought I was NUTS!

Especially Valerie, who found it impossible to sing over.

As history shows, we worked that out.

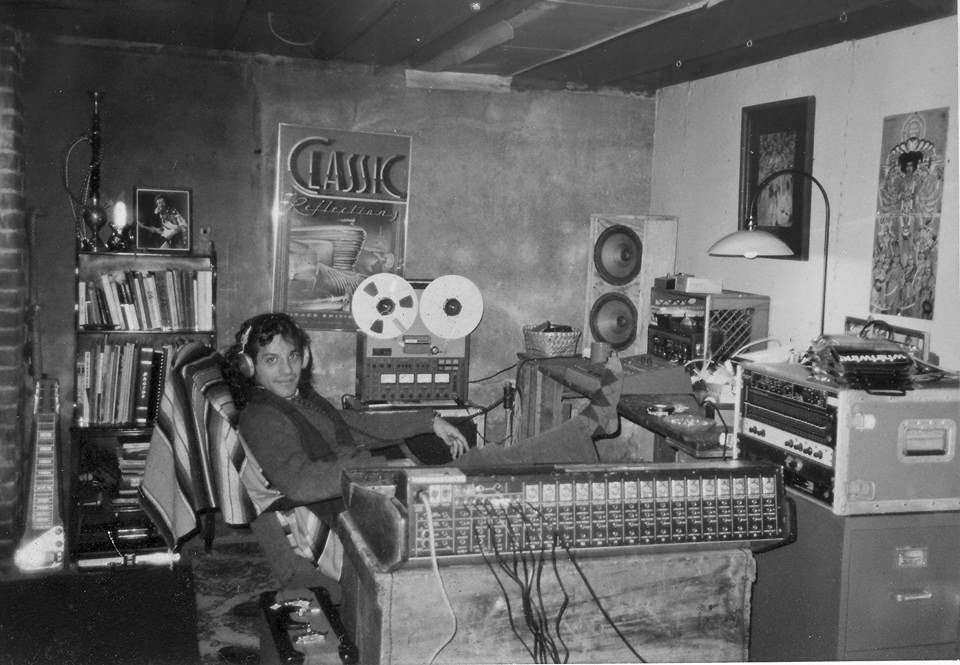

Our engineer was Fritz Richmond, who was a former member of the Jim Kweskin Jug Band and still played with Maria Muldaur. He was one of the bright lights of the Greenwich Village folk scene of the late '50s/early '60s. We didn't know who he was until years later. I could go on and on about Fritz.

Fritz Richmond with Maria Muldaur and Jim Kweskin Jug Band

Often during the making of "That's Right," it was just Fritz and I alone in the control room. We cut the guitars direct, straight into the board, no amp involved. I was frustrated by all the little clicky noises the guitars made.

"I hate recording!" I said.

"Recording is FUN!" Fritz says.

That's the kind of guy he was. Sometimes, he would show up wearing funny hats, bowlers, and tam-o'-shanters. And he was a calming presence, like a great pediatrician.

I ended up stuffing a bunch of toilet paper down at the first fret, and that cut out most of the noises. Later, when I could hear what compression was, I realized that Fritz had really whomped down on those guitars. That's why they sound like a record.

For a great example of what compression sounds like, listen to the guitars on the Beatles' "Baby You Can Drive My Car."

The clap sound on the LINN DRUM was a weak little KACK. Nothing like the big disco clap on ZAPP! Records. We fooled with that for a while. Fritz put a tight delay on it, maybe 22 milliseconds, and turned up the feedback so there were three or four repeats, so instead of KACK, we had the very satisfying THRAPP we all know and love.

Then we recorded vocals. The backup singers were Valerie, her sister Shannon, and Lori Lamphear, a 1980 NUSHOOZ alumnus. We were meticulous about the pronunciation of certain words. We spent hours and hours on this. A good example is how they swallow the 'T' on the word 'WAIT.'

Another feature of the vocals is the quarter note delay on Valerie, which gives the lead vocal a psychedelic dreaminess even if you don't notice it right away. The syncopated vocal lends itself to a straight delay time, whereas a less syncopated line would suggest a dotted 8th note delay.

After all that work, the track still sat there. Then I was listening to Jungle Love by The Time. That track had some bottles for percussion. I came up with a stereo bottle part and a stereo tambourine part, and then the track really started to roil and boil. It was the final touch…almost.

THE REMIX

The sample at the beginning of the I.C.W. 12" [which we affectionately call "the Barking Seal"] was played by Dutch D.J. Peter Slaghuis on an EMU EMULATOR II. The model II still used those big 3" floppies, like a Commodore 64. Over the years, people have told me what the sample was, but I can never remember.

He achieved the stutter effects [I-I-I-Can't Wait] by actual tape-cutting with a razor blade and editing block. I watched him cutting tape at Atlantic Studios in NYC. He had some good tricks, but he was very shy, didn't speak very good English, and didn't like people around when he worked.

So…

That's all the technical musical hardware and anthropology that I can recall. It's amazing that people are still interested in this song forty-plus years on. You can see what a bare-bones process it was, And what a miracle it is. Thanks for the letter.

John R. Smith

NUSHOOZ

11.28.23

P.S. Forty years later, we learned that Peter Slaghuis, who did the famous ‘Dutch Remix’, didn’t like the song, so he didn’t fool with it very much. His dream was to do remixes for ABBA…which is about as far away from Nu Shooz as you can get!

It's A Nu Video!

MAGIC & MUSIC COLLIDE! Watch our spellbinding new video for "YOU PUT A SPELL ON ME" from Kung Pao Kitchen! Portland's wizard of weird, Mike Wellins (the genius behind Portland’s PECULIARIUM), works his visual magic with a clever magician's rabbit as the star. This trippy journey perfectly complements John Smith's "answer song" to Screamin' Jay Hawkins' classic. As Mike says, "The future is here" - and it looks delightfully strange!

HERE'S A NU VIDEO FOR YOUR VIEWING PLEASURE!

It's "YOU PUT A SPELL ON ME" from our album Kung Pao Kitchen. It was made by the phenomenal Mike Wellins. Mike is the brains behind Portland's PECULIARIUM, his museum of curios, monsters, magic, and ephemera. This is his third video for the Shooz. (The other two are "SPY vs. SPY" and "BAGTOWN.") He made this one using AI technology. His unique sense of humor is evident throughout. The use of a magician's rabbit as the star is brilliant!

"SPELL" was written by John Smith using an old songwriting trick called "The Answer Song." When the Motown writers got a hit with "My Guy," they followed it up with "My Girl." You get the idea. So "SPELL," while not a true answer song, was a vector off the old Screamin' Jay Hawkins song "I PUT A SPELL ON YOU."

We're so grateful to have talented people like Mike in our orbit. He obviously had fun with this one. As he said, "The future is here."

"YOU PUT A SPELL ON ME" ©1992, 2012 John R. Smith, Margaret Linn

PRODUCED BY ALPHA LANG FOR EVOLUTIONLAB

Arranged by John Smith, Jeff Lorber, Margaret Linn

Recorded in 1988 at JHL Studios, Pacific Palisades, CA

Remixed in April 2012 by Gregg Williams at The Trench, Portland, OR

MUSICIANS:

Valerie Day — Lead and Background Vocals, Congas, Percussion

Tracey Harris — Vocals

Margaret Linn — Vocals

Jeff Lorber — Keys, Percussion

John Smith — Guitars

Cassette

Remember cassettes? Those humble plastic rectangles that revolutionized how we listened to and created music? While they may seem primitive by today's standards, these analog warriors played a crucial role in shaping the Nu Shooz musical landscape. From mixtapes and portable music to DIY recording, cassettes weren't just storage devices - they were magical little time machines that changed everything. Let us take you back to an era when the hiss of tape was the soundtrack to innovation...

Image by Bruno from Pixabay

We used to look down on Cassettes. Ten years on, they seemed to lose their high-end frequencies as the iron oxide coating sloughed off the plastic strip. But in the end, we were in for a surprise.

Just TRY to get back to that song you stored on a floppy disc back in 1992, that thing you recorded in Cubase or StudioVision. Back then, if you were an audio engineer, I bet you logged all the mix data like a Benedictine scribe.

Now, here we are in the twenty-first century.

Just TRY to get back to 1992. All the little connectors have changed. Our computers lack disc drives. Not to mention CD drives. The new stuff has no holes or portals or whatever you want to call them to plug the old software in. Your 1992 MIDI file can no longer be read by the current OS.

So, guess who wins?

The Cassette.

The lowly maligned Cassette.

I take back every bad thing I ever said about them.

Compared to all those digital signals you can no longer decode, these plastic rectangles sound wonderfully ANALOG…they bear the whiff of TIME TRAVEL.

A friend of ours, a big Viking named Kevin, turned us onto a documentary called…wait for it…CASSETTE. It was made in 2017. Here it is on YouTube. The main character is an engineer in Denmark named Lou Ottens. In the film, he’s 82 years old. He led the team at Philips that invented the cassette.

The basic idea was that reel-to-reel tapes had to be thicker because they were always being manipulated by human hands. If the tape didn’t have to be handled, it could be smaller and thinner. Dr. Ottens was humble about his own contributions. He led the team. Other people handled the engineering and the aesthetics.

We recommend this film, especially if you were present at the creation. The Cassette changed everything! It was a miracle. You could carry it around.

The Philips team was aware of the fact that Sony was developing the Walkman. At some point, Lou Ottens flew to Japan and met with Sony executives. “We have to agree on a standard format,” he said. “Or else there will be chaos.”

Sony agreed.

The Cassette and the Walkman entered our 20th Century lives at roughly the same time and changed the world in so many ways.

For starters, you could tape other people’s records!

It was the birth of the mixtape.

In 1970’s money, good-quality cassettes were expensive, but you could get cheap ones three-for-a-buck…(Ha! Like Top Ramen!!!) So that’s what we mostly recorded on back in the day.

It’s hard to imagine now, in this era of instant free access to the musical universe, but albums were these precious objects. They cost anywhere from seven to twelve bucks (in 70’s money,) and often, one bought them unheard!

So, if you had a friend with some vintage Coltrane or Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, you sprang for a nice new cassette and raided your friend’s collection. Often, we would draw our own cassette covers! It’s hard to convey how absolutely groovy this was.

And once you taped it, the music was PORTABLE! It’s not like you can walk down the street listening to a stack of LPs.

I was just a junior birdman back in 1975, when I got the bright idea to record a backing track on one cassette deck, then play it back and play along onto a second cassette.

Woo, magic!

I’m not the first guy to do this, for sure. (Reinventing the wheel has always been my modus operandi.) Anyway, every time you go up a generation, the pitch goes up slightly, and you get another bucketful of tape hiss. Each generation of fuzzy background vocals gets higher and higher.

Think Alvin and the Chipmunks in a snowstorm.

One morning, Valerie came downstairs looking slightly irate.

“Who are those girls you brought in to sing on that tape?”

I shrugged.

“It’s just me and the Chipmunks.”

That’s all we had back in the late ’70s.

It took a year to write a song sometimes. There was no way to make it hang together in your head, to make it stand up and walk around by itself. (I’m talking about funk songs here.) Drum machines were in their infancy. We made fun of the Roland 808 back then. It was later to become an essential element of Hip-hop. And anyway, who could afford one?

That’s when I discovered the OMNICHORD.

Valerie’s mom, Janet Day, was a celebrated opera singer in the ’50s and ’60s. By the time NU SHOOZ was up and running, she was into Christian music. One day, she came home with this thing called a Omnichord. It looked like a cross between Mabel Carter’s zither and a white Fender guitar pick. It was completely electronic and worked like a zither, I.e., one hand fingering preset chords and the other hand ‘strumming.’

To my delight, it also came with a drum machine!

Close your eyes and imagine the drum beats in those old Home Organs: Swing 1 & 2, Bossa Nova 1& 2, and most important, Rock 1& 2. I recorded these beats at a bunch of different speeds to cassette. At last it was possible to get a little machine help in the songwriting process.

By this time I had a cheap knock-off Walkman, and I spent hours circling the neighborhood writing songs over these tapes.

John’s Walkman and carrying case from the early 80s.

Another gift that came with the advent of the cassette was you could tape your own gigs and listen back to them without having to drag around a heavy reel to reel.

Thank you, Dr. Ottens!

Like I said, good cassettes were expensive in ’70s money, so we would re-use the gig tapes. And I’m guilty of burning a lot of live tapes because I hated my singing. I wish I had some of them now. You think certain eras of your life will last forever. Oh, if we were more like the Grateful Dead and saved every live tape…there would be some amazing stuff there. But maybe those days live much better in memory.

In Portland at that time, R&B records were, to quote Bob Dylan, “as rare as hen’s teeth.” The Classic four-horn NU SHOOZ band of 1980-82 was on fire in the clubs, and I was desperate for material. In addition to the absence of R&B records, Portland had zero R&B radio!

I grew up in San Pedro, California, listening to the Black AM station KGFJ 1230. My mother still lived down there, so whenever I visited her, I would tape the radio. I still have those tapes from 42 years ago. Talk about time travel!

I could go on and on about the impact of the Cassette on our musical lives. Our rehearsal tape deck, named the ‘Wilmalator,’ is immortalized on the 1981 NU SHOOZ t-shirt. Sadly, the machine itself is now just a memory.

The Wilmalator graphic.

We recommend the CASSETTE documentary. The story is fascinating: a small group of Dutch engineers who changed our lives forever.

Fan Questions: Tales from the Studio - Remember Those Analog Days?

What do granny glasses, pet rabbits, and wonky cassette players have in common? They're all part of our adventures in the analog recording world. Get ready for some studio stories that'll make you grateful for digital.

Dear NU SHOOZ, can you talk about some difficult recording studio experiences?

Anthony

Tampa, FL

Hi there, Anthony,

You asked about difficult recording experiences. So here's a few.

1. This doesn't come under the category of 'difficult,' but it was formative. When we recorded the original 'American' mix of "I Can't Wait," the audio engineer Fritz Richmond said, "Is this going to be a single?"

And we were like, "Single? What's that?"

He ended up cutting the intros and verses and "middle-8s" in half and made some breakdowns without which the famous version of "ICW" wouldn't have been possible. He did this by cutting up the 2" master tape with a razor blade on an editing block. There was no digital audio back then, and that's how it was done.

Fritz Richmond was this incredible, super-humble guy. You'd never know he was part of the Greenwich Village folk scene and actually started the whole 'granny glasses' thing. He never brought any of that up while we were recording - that's just the kind of person he was.

He’s deserving of a whole blog post of his own. Someday soon, we’ll write it.

Fritz with his washtub bass and granny glasses.

2. We were down in L.A. at Sunset Sound Factory recording "Should I Say Yes." We couldn't get a vocal take that I liked better than the demo. Eventually we decided to use the vocal from the demo tape. The problem was, the demo vocal was on 1/4" four track and the master was 2" 24 track. Also, they were running at slightly different speeds. And there was no time code. So we had the demo FedExed down from Portland, set up a machine and 'flew in' the vocal one phrase at a time. To do this Jeff Lorber marked a place on the demo tape with a grease pencil, played the master and hit go on the other machine. It would take several attempts before it landed in the right place. We did the whole song like that.

Sunset Sound Factory

Jeff Lorber

3. At some point in the making of a record, we'd have to make a cassette and take it in to the A&R department at the Label. The problem was, the people at the label always had the crappiest stereos, and no two cassette players ran at the same speed. This was way before CDs or DATs. So we're sitting with whoever and the tape is either running too slow or too fast, quaaludes or helium, and everything sounds stupid.

image by Feodor Chistyakov

There you go. Thanks for the question. There are so many more. Like the all-nighter I pulled for a band I was producing. Next day, I found out it was the wrong tune!

Like the pet rabbit, Gary who liked to chew on the cables and eventually died for his bad lifestyle choices.

All the best,

John R. Smith

Nu Shooz

THE GOLDEN AGE OF THE PORTLAND MUSIC SCENE

It's our humble opinion that Portland, Oregon, for a brief period in the 1980s, had the best music scene IN THE WORLD.* I should qualify this by saying we only had New York and L.A. to compare it to: New York, where famous jazz guys were making fifty bucks a night, and L.A., where you had "Pay to Play." [I.e., Sell tickets to get a slot on the club stage, where you'd get exposure and hopefully gain the attention of an A&R man from a major label. People die of exposure.]

Portland was different. For a Golden Period, from around 1980-86, dozens of clubs opened. There was a brief relaxation in Oregon’s strict liquor laws. This came at the exact moment when Nu Shooz changed from a struggling four-piece to a nine-piece band with four horns.

The Key Largo calendar circa 1984.

It’s our humble opinion that Portland, Oregon, for a brief period in the 1980s, had the best music scene IN THE WORLD.* I should qualify this by saying we only had New York and L.A. to compare it to: New York, where famous jazz guys were making fifty bucks a night, and L.A., where you had “Pay to Play.” [I.e., Sell tickets to get a slot on the club stage, where you’d get exposure and hopefully gain the attention of an A&R man from a major label. People die of exposure.]

Portland was different. For a Golden Period, from around 1980-86, dozens of clubs opened. There was a brief relaxation in Oregon’s strict liquor laws. This came at the exact moment when Nu Shooz changed from a struggling four-piece to a nine-piece band with four horns.

There were ten clubs within a mile radius of downtown. We worked every weekend for seven years. Nobody was getting rich, but our lives felt rich. And it was a unique situation at that time. The Last Hurrah, for instance, wanted sixty percent original music, and that’s what the audience wanted, too.

A video has just surfaced that describes the joy of that era and what brought it to an end. It’s a Cable Access show filmed in 1987 called PDX Rocks, hosted by Pat Snyder. Pat was one of the main photographers capturing that world as it unfolded. In this clip, she’s interviewing two of the most important club owners from that period, Peter Mott (The Last Hurrah) and Tony Demacoli (The Long Goodbye, Luis La Bamba, Key Largo.) Their contributions to that scene AND to the career of NU SHOOZ are beyond measure.

A few of the bands eventually got record deals and dropped out of the club scene. Billy Rancher, one of the biggest local stars, was about to be signed when he died of cancer. According to Peter Mott, all this siphoned off a lot of the top talent.

But other forces conspired to bring that golden period to an end. A recession drove up unemployment. The price of liability insurance for the clubs exploded by 600%, and as Tony pointed out, people had other entertainment options. Cable T.V. and the VCR reached critical mass around 1982, and I swear, you could feel it from the bandstand. The audience was staying home.

No scene lasts forever. We were lucky to live in a time period when it was great to be young musicians. And we’re grateful for intrepid club owners like Peter Mott and his brother Michael and Tony Demicoli, who worked so hard to make that scene happen and made our artistic lives possible.

*I guess Manchester, England, had its own Golden Era around the same time, but that was a faraway land, and it was pre-internet.

Nu Shooz Interview On Night Traxx Radio

Recently, we had a delightful interview with the one-and-only Teddy Bear from Night Traxx Radio, and what a teddy bear he is: a big man with a velvet voice. We liked this one a lot, partly because he didn't ask the usual questions. Instead, he wanted to talk about the creative process and, most interesting of all, how a person maintains their mental health in such a crazy business.

Recently, we had a delightful interview with the one-and-only Teddy Bear from Night Traxx Radio, and what a teddy bear he is: a big man with a velvet voice. We liked this one a lot, partly because he didn't ask the usual questions. Instead, he wanted to talk about the creative process and, most interesting of all, how a person maintains their mental health in such a crazy business.

We did an interview together a couple of months ago, which, unfortunately, was lost in the digital void. But that's OK because it was long enough ago that we forgot everything we said! We enjoyed our time with Teddy Bear so much that we were happy to do a retake.

You can listen to the interview on Blog Talk Radio or watch the video below.

Stealing Like an Artist: The Creation Story of Driftin’

Dive into the creative process behind Nu Shooz's 'Driftin,' an 80s song that embodies Austin Kleon's philosophy of artistic influence and transformation.

In 2012, Austin Kleon wrote an influential little book called ‘Steal Like an Artist.’ “What a good artist understands is that nothing comes from nowhere. All creative work builds on what came before. Nothing is completely original.”

The Nu Shooz song ‘Driftin’ is a perfect example of this kind of thinking in action. The song was written in 1987 for the Shooz’s second Atlantic album ‘Told U So.’ My songs usually start with a nice set of chords. ‘Driftin’ was based on two chords one of my friends used to play. I often name music bits: the BB King Lick, the Watchtower Progression, the Stevie Wonder Thing, etc. So the first two chords in Driftin’ are the Azul Chords, named after my late friend and fellow songwriter, Azul Amey.

The harmony (on the word Driftin’) came from some R&B tune I can’t even remember. I just knew I could use that bit for something. And it was that tiny piece that put the song into the Ballad box. Lastly, there was a Jimi Hendrix song called ‘Driftin’ on his album ‘Cry of Love.’ I can’t remember how that piece of DNA drifted into the songwriting process, but that one word fit everything else that was going on…

I remember exactly where I was sitting when this was all coming together. It was late spring. I had a cute little Gibson B-25 on my lap. I’m playing the chords and trying to stuff every nautical oceanic seafaring thing into the lyrics. And during this whole process something happened that was more than stealing. It’s more like borrowing a few lumps of clay from fellow artists, taking it back to the potter’s wheel, spinning and kneading it till it becomes something completely new. My version of Driftin’ bears no resemblance to Jimi’s, but he was definitely along for the ride.

We loved this song so much that we recorded it twice: first in 1987 on our album ‘Told U So’ and then in 2010 on ‘Pandora’s Box.’

FAN QUESTIONS!

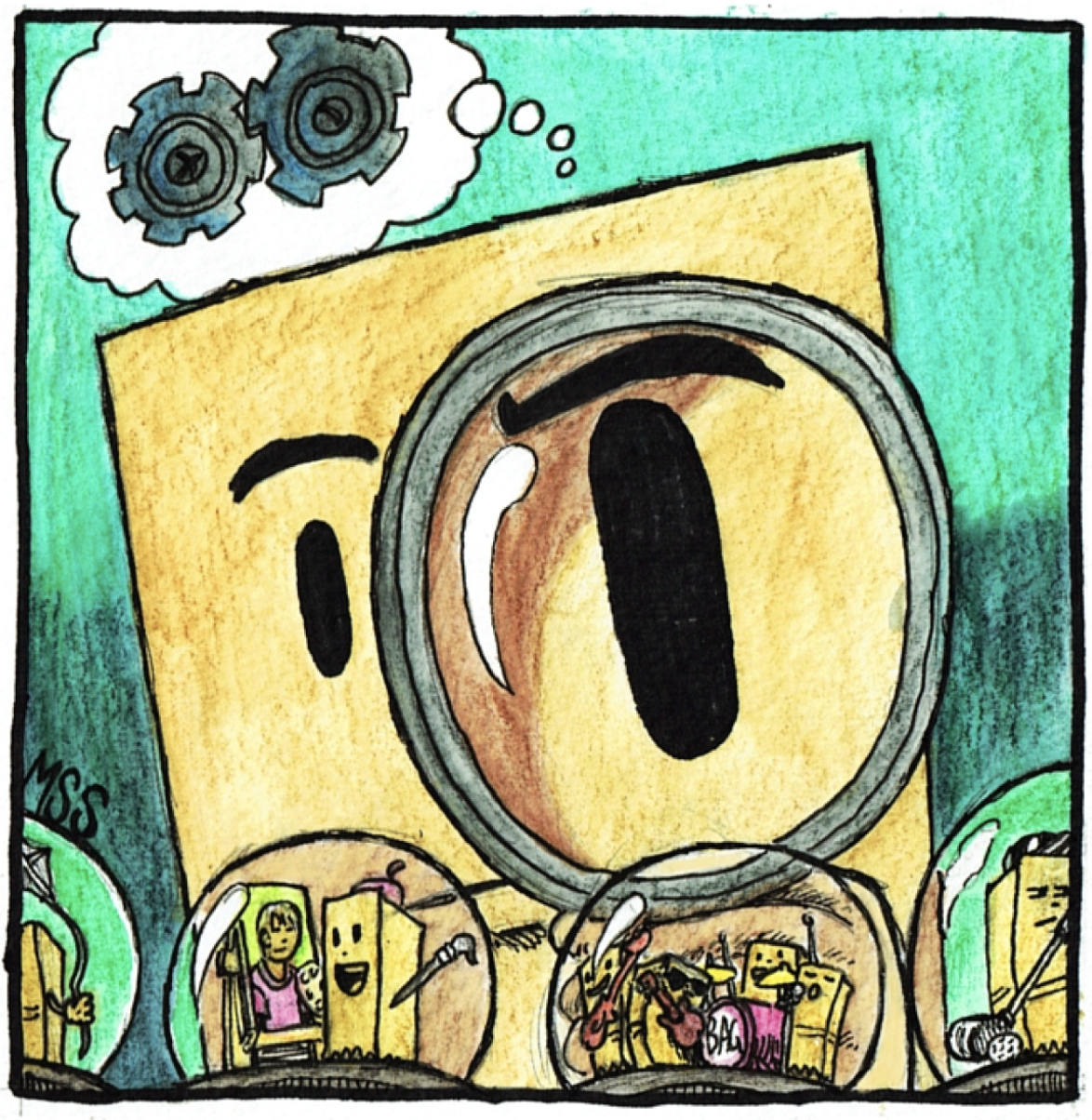

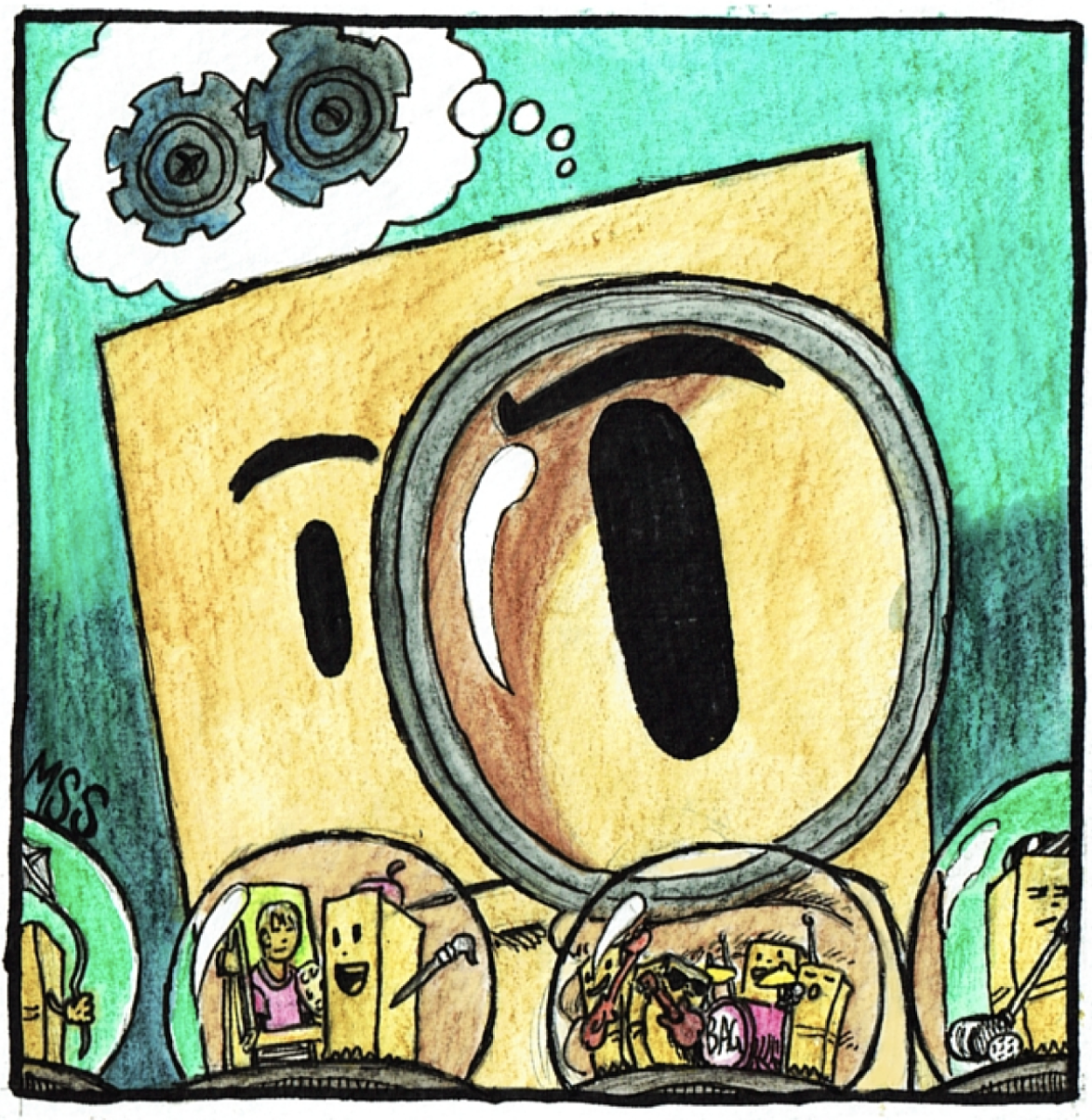

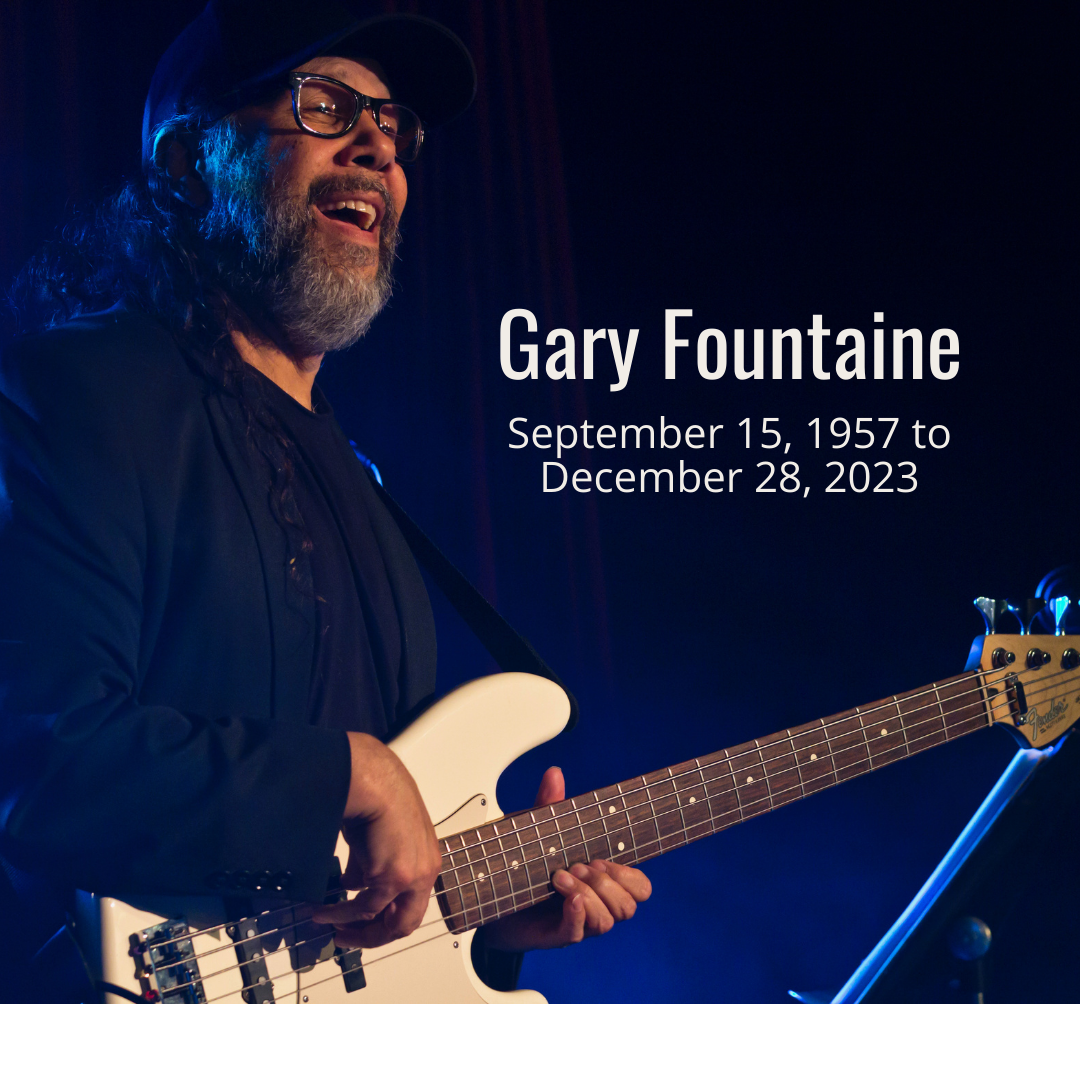

Andy writes, "Hey guys - I hope you can answer this for me. Was Gary (Fountaine) the original bass player from back in the early 90’s?”

Great question! Read on to discover the untold history of Nu Shooz's bass players, from the band's beginning to their last performance in 2017. Head into the time machine with tales of funky gigs, band shake-ups, and unforgettable music. This piece pays special tribute to Gary Fountaine, the band's longest-serving bassist, who brought joy to every performance.

Art by Malcolm Smith

Andy writes, "Hey guys - I hope you can answer this for me. Was Gary (Fountaine) the original bass player from back in the early 90’s? Just reminiscing and remembering back when I worked in a computer shop and was on one of these camera chat programs (hi-tech back then) one evening. It basically just gives you someone to chat with, and I got this guy sitting there with a bass guitar in his lap. He could hear me talking, but I couldn’t hear him. That’s when he moved the camera closer to a golden record on the wall, and it said Nu Shooz. As a huge fan, I was totally starstruck."

O.K. Here’s the answer!

The first Bass Player in NU SHOOZ was JIM HOGAN. At the time, he was also the best-looking member of the group. He was a trombone player as a kid (just like Berry Oakley of the Allman Bros) and, therefore, musically literate. Jim has a key role in Nu Shooz’s history.

Our drummer, Randy, son of a music store owner, was good at finding gigs.

(L. to R. John Smith, drummer Randy Givens, bassist Jim Hogan, and guitarist Larry Haggin.)

We were just barely putting a set together when he got us a gig at the park half a block down the street. Colonel Summers Park in Portland, Oregon. So now our band had a gig, but we didn’t have a name.

We’re in the kitchen of the house where we practiced.

We called it Twenty-One-Twelve.

There was this wallpaper above the stove, like old newsprint, and we all looked over and saw these button-down shoes. Hey, we could be the Shoes. Stupid! Cool!

A week later, we’re in a record store, and we see an album by this band from Ohio called SHOES. I don’t know why, but leaving out ‘the’ bugged me for whatever reason.

Enter Jim Hogan.

“Well,” he says, “We could be New Shoes!” and we should spell it with a ‘Z’ because it’s MORE ROCK.”

Without Jim, we wouldn’t be NU SHOOZ.

He played in the band from May ’79 to around the Summer of 1980.

(Jonathan, back row, third person from the left, on the back of our 1982 album, Can't Turn It Off)

Our SECOND bass player was JONATHAN DRESCHLER. Jonathan was a really good R&B, Motown, and Soul player. He could play that STAX stuff, especially. We stole him from another band. He was perfect for that incarnation of Nu Shooz. Jonathan played with us from 1980-82.

Bass Player Number Three: RANDY MONROE.We had this great drummer, Towner Galaher, who could TOTALLY play that Tower of Power stuff. He LOVED their drummer, Dave Garibaldi, and that’s the stuff we were playing in 1981. He threatened to quit if we didn’t replace Jonathan with his friend Randy. It’s painful being a bandleader sometimes.

Randy got to be there for the Roaring ’80s, and the word ‘FUNKY’ sells his bass playing way short.

(Randy Monroe and Towner Gallaher, 1982, Civic Stadium, Portland, OR.)

Towner and Randy kicked the band up five levels. You can’t fake that kind of thing or wish it into existence.

In ’82, we accepted an offer from a Top-40 agency for a chunk of money to tour up in Montana, Idaho, and Northern Washington for six weeks. Sixteen hundred bucks a week sounded like a lot of dough, but split Twelve ways? Hmm.

This whole story has been told elsewhere, but when we got back to Portland, another band took our place at the Last Hurrah. Five people quit, including our rhythm section, Towner and Randy, and one was fired. For a minute, NU SHOOZ was down to me, Valerie, and our Trumpet Player, Lewis Livermore.

BASS PLAYER NUMBER FOUR- GARY FOUNTAINE.

We met Gary when he was thirteen or fourteen. Valerie and I met and lived for a while at a Hippie Commune on Twenty-Third and Kearney in Portland called the Cosmic Bank. Gary lived three blocks down with his big brother Ed.

A long time later, we learned that their father was one of the great bass players in the Portland music scene of the 40s and 50s. The family still has his bass, in bad disrepair. If you drive up Weidler into Northeast Portland, there’s this strange street triangle...and THAT was the beginning of the Black NIGHTLIFE scene. It ran for eight or nine blocks farther North.

The 1940s PORTLAND BLACK NIGHTLIFE SCENE thrived because the train station was three blocks away. The Pullman Porters, as it turns out, were not paid all that well, but they formed a kind of upwardly mobile stratum of Black Society.

They had ‘WALKING AROUND MONEY.’

What that battered bass must have seen.

When we met Gary, he already knew he wanted to be a Bass Player.

His brother Edward, a couple of years older than us, knew more chords than we did.

Gary was playing ‘bass’ on a Harmony Sovereign, a folk guitar. This was a weird era in the mid-70s when there were these two virtuoso bass players on the scene, Stanley Clarke and Jaco Pastorius, playing fast and busy as all get out, playing Jazz Guitar, not bass. With all due respect, I felt like they ruined all bass players for a while.

Anyway, in 1975, Gary was playing really fast with one finger — dugadugadugaduga.

Gary knocked around the scene. We lost track of him for a while.

Then, in ’83, our whole band Quit or was Fired. Our nine-piece band was down to three when we hired Gary.

GARY FOUNTAINE WAS OUR BASS PLAYER FROM 1983 TILL OUR FINAL BAND APPEARANCE AT ‘80’S IN THE SAND’ IN THE DOMINICAN REPUBLIC IN NOVEMBER 2017.

Gary onstage at 80s In The Sand, Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, in 2017.

Nu Shooz Bass Players Reunion, 2012. L to R: Randy Monroe, Gary Fountaine, and Jonathan Drechsler.

Got a Question for The Shooz?

Just head on over to our CONTACT PAGE and we’ll try to respond in a future newsletter.

Farewell to our longtime bass player and friend, Gary Fountaine. September 15, 1957 to December 28,2023

We lost a good friend recently. Our beloved Bass Player Gary Fountaine died of cancer on Dec 28, 2023, at the age of 66.

There are certain players and singers who put out 110% every night, whether there’s five people in the audience or 50,000. THEY LEAVE IT ALL ON THE STAGE. Gary was one of those people. Joy emanated from his corner of the stage, whatever band he played with. He was so happy to be there. He loved his instrument. He loved the music and the audience. It was never fake.

Everybody knows the real thing when they see it, and Gary Fountaine was the real thing.

We lost a good friend recently. Our beloved Bass Player Gary Fountaine died of cancer on Dec 28, 2023, at the age of 66.

Gary was just a kid when we first met him, thirteen or fourteen. He already knew he wanted to be a bass player, but he didn’t have his own bass yet. I can still picture him the day we met; he was playing Stanley Clarke riffs on a beat-up Harmony Sovereign. Back then, he had this crazy one-finger technique.

We lost track of him for a while. In the meantime, Gary developed into the accomplished bass player we know and love. He played in a million bands. There were lots of places to play in those days. Gary didn’t read music. He told me once that he kept track of all the different set lists by compartmentalizing them in his brain.

Gary used funny terms like “Ice Cream Changes” and “Lumpty Gigs.” He also taught me things about being a father, things I remember to this day.

There are certain players and singers who put out 110% every night, whether there’s five people in the audience or 50,000. THEY LEAVE IT ALL ON THE STAGE. There are a lot of clips of Gary on YouTube right now. (You'll find a special one below.) You can see the joy that emanates from his corner of the stage, whatever band he’s playing with. He’s so happy to be there. He loves his instrument. He loves the music and the audience. It was never fake.

Everybody knows the real thing when they see it, and Gary Fountaine was the real thing.

Goodbye, old friend.

![Welcome to your summer. Yes, it's finally here! And it's the 46th anniversary of the very first NuShooz gig. [Colonel Summer's Park, Portland, Oregon, June 21st, 1979.] What a different world that was; pre-internet, no smartphones or smart toasters,](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54cee645e4b01fa0f0bfc5f9/1772327896063-IIMMIJOZCTP00HOVTU9D/image-asset.jpeg)