Everything About The Making Of I Can't Wait

Did you know 'I Can't Wait' was originally much faster? When we slowed it down to 104 BPM in the studio, the band thought John was crazy! But that slower groove, combined with some engineering magic and creative percussion (including wine bottles!), helped create the sound y’all know and love.

The most frequently asked FAN QUESTIONS are about the making of “I Can’t Wait.” So, here’s an attempt to include every technical detail about how we made that song forty-one years ago. It’s amazing that we’re still talking about it almost half a century later!

The recording of “I Can’t Wait” perfectly captures that unique moment in music history when analog and digital technologies were colliding. Looking back, it’s amazing how we managed to create such a rich, layered sound with relatively simple equipment. Every decision - from the LINN drum machine to engineer Fritz’s compression techniques - helped shape what would become Nu Shooz’s signature hit.

Subject: I Can't Wait production

Message: Hello Valerie and John! I was listening to "I Can't Wait" today and would love to know how the song was produced. Equipment. Instruments. Etc... Has this information ever been shared in an interview somewhere that I can look up? Thanks for this wonderful classic. — Patrick

Hi Patrick!

Thanks for your letter. We get asked this question a lot, so I'm going to write down the definitive version of THE MAKING OF 'I CAN'T WAIT.'

EVERYTHING ABOUT THE MAKING OF NU SHOOZ 'I CAN'T WAIT' (That we can remember.)

It was the winter of 1983, a time almost unrecognizable now. TV still signed off at 2 a.m. Cable was just getting started. And none of the gear existed that we take for granted now. MIDI was new and prohibitively expensive. NU SHOOZ had a horn section but no keyboards.

Without MIDI or a multitrack, it was harder to write songs, to make them stand up and walk around by themselves. We were playing all the time, almost every weekend, and this created an insatiable need for new material. People would leave the band and you couldn't play this or that song anymore. The new guy would come in, and we'd have to teach him all the moldy oldies. There were songs I was so tired of that it hurt to play them. And in Portland, funk records were hard to find. So, I had to become a full-time songwriter. In the Brill Building days, writers like Carole King and Jerry Goffin made hit songs by putting in the hours—showing up every day.

I started writing songs in batches of ten. How it worked was, I'd number one to ten on a piece of paper and then slot in a bunch of tempos, like this:

Mid-tempo [meaning funk]

Mid-tempo

Fast

Mid-tempo

Slow

Fast... etc

Next, I would assign a Kick/Snare pattern to each number. When you're writing songs, specifically Funk songs, you become a connoisseur and collector of Kick/Snare patterns. Some of my personal favorites are Surf Beats for fast stuff, and anything by Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis for the FUNK.

I got a lot of Nu Shooz Kick/Snare patterns from the Grandmaster Flash album 'THE MESSAGE.'

I tried to finish two songs a week for Wednesday rehearsal. I.C.W. was one of the first songs to come out of this batch writing process.

As I said before, it was hard without any gear to make a song hang together in your head. My Mother-in-Law had this thing called an OMNICHORD. It looked sort of like a zither, but it was completely electronic. It had a little drum machine in it, you know, like those old 'Home Organ' beats: Swing, Waltz, Bossa Nova, etc. And there was one called ROCK BEAT 1.

I plugged the OMNICHORD into a cassette machine and recorded ROCK BEAT 1 at a bunch of different speeds. This worked for all the tempos mentioned above. This was a vast improvement. Before that, I was trying to make drum beats by banging on a kitchen table with dinner plates on it.

Then I begged our manager to rent a ¼" four-track machine from the local sound company. For the princely sum of $24 a month, they rented us a TEAC 3440. Great machine. [I still have it, by the way.] Right away, I filled a tape with my OMNICHORD beats, and just like that, I was in business. Writing songs was suddenly so much easier.

I.C.W. was written while sitting on a wooden stool next to the furnace in our basement rehearsal space. The bass line was composed on a 1965 Fender P-Bass [Black/Rosewood Fretboard/Tortoiseshell guard] belonging to our Soundman. The Bass was tuned to Drop-D. The chords were played on a cheap [but nice] nylon string guitar called a DISCOTECA SERRANO.

I mixed the demo to cassette, put it in my Walkman, and spent the next month or so walking around and around the block. The first chorus bit that I heard in my head was:

"I Can't Wait till FRIDAY NIGHT"

Eventually, that morphed into the call-and-response:

'Cause I Can't Wait

BABY

I CAN'T WAIT.

Phew!

So now that the chorus was "sitting still," the song needed verses.

My love— The first two words of a Lionel Richie song

Tell me what it's all about— A line from my Bone Pile

You've got something

That I can't live without— A vague come-on

Happiness— The first word in an Alan Toussaint song

Is so hard to find— My answer to his line

Etc., etc.

Back then, I was good at one-and-a-half verses.

Anyway…

We had a Wednesday rehearsal coming up, and I didn't have anything but this half-finished song. The band was actually loading their gear into the basement. Valerie was standing at the sink, and I was at the kitchen table. In ten minutes, I wrote the rest of the song. There! I shoved the paper at Valerie.

She said, "Good enough."

There was just enough time left to scribble up a horn chart.

So now it's 1984, and we're playing I.C.W. in the clubs. We called it a B-level dance song. People danced to it, but we played it way too fast, just to get it over with. Around that time, Rick, our manager, called.

"We need to record something. I need something to market."

He didn't like our first album, "Can't Turn It Off," and he was right. It didn't represent the band anymore. Rick had just inherited five grand from a deceased aunt, and he wanted to bankroll a Nu Shooz album.

He asked me, "Do you have any songs you like?"

"Well," I said, "the one that sounds the most real is 'I Can't Wait.'"

By real, I meant that it sounded the most like a real record. Valerie sounded great on it right away. [Her voice worked perfectly an octave above my songwriter croak.]

Rick booked us into Cascade Studio in Portland, Oregon. Sessions began in the summer of 1984. Before we went into the studio, I was pondering whether or not to use a drum machine. We used to make fun of the early ones. The ROLAND 808 only became popular with the advent of Hip-Hop. We tried cutting the song with a live drummer first, and that just didn't work. We had to have that machine kick/snare/clap…like ZAPP!

For a band that couldn't afford keyboards, a drum machine was out of the question.

Fortunately…

We knew a rich guy who didn't play but had a house full of all the best gear.

He owned a LINN LM-1.

The LINN LM-1 was Roger Linn's first commercially available drum machine. It was so much heavier sounding than an 808. It retailed for $5,000 [in '80s money!]

Next, we put on a bass.

Live bass didn't cut it, either. So we hired a bass player, Nate Philips, who owned a MINI-MOOG. He was one of the great Portland funk players, going back to the '70s band Pleasure. Nate dialed in the sound and played the part. I got my own MINI-MOOG not long after that, but I never could get close to the sound that he made.

The piano was a seven-foot Steinway.

The guitars were a cream-white [nicotine yellow] 1969 Fender Stratocaster and my number one fave 1967 Gibson 335 [battered black].

This is it — John’s 1967 Gibson ES335.

The horns are real, just trumpet and tenor doubled.

Our saxophone player, Dan Schauffler, had just bought a ROLAND JX-3P synth. It had eight preset sounds, and I'm pretty sure we used them all. A good example is the chime in the intro, which was kind of a take-off on "Tubular Bells" by Mike Oldfield, and the legato synth string line that follows. The JX-3P was one of the first commercially available MIDI synths. Everything was new back then.

The Roland JX-3P in all it’s magnificence.

Cascade Studio had a two-inch 16-track machine, which was and is kind of rare, then and now.

It was a real stroke of luck for two reasons. First of all, the tracks are wider than a 2" 24-track, and they actually have a fatter sound. And second, we didn't have those eight extra tracks to clutter up the song.

Before we had anything on tape, I had an epiphany and realized that it would be so much funkier if we slowed it down. I tramped around the studio parking lot, singing the bassline, feeling for where the funky place was. Then I ran back into the control room. We slowed it down to 104 bpm from however the hell fast we were used to playing it.

The band thought I was NUTS!

Especially Valerie, who found it impossible to sing over.

As history shows, we worked that out.

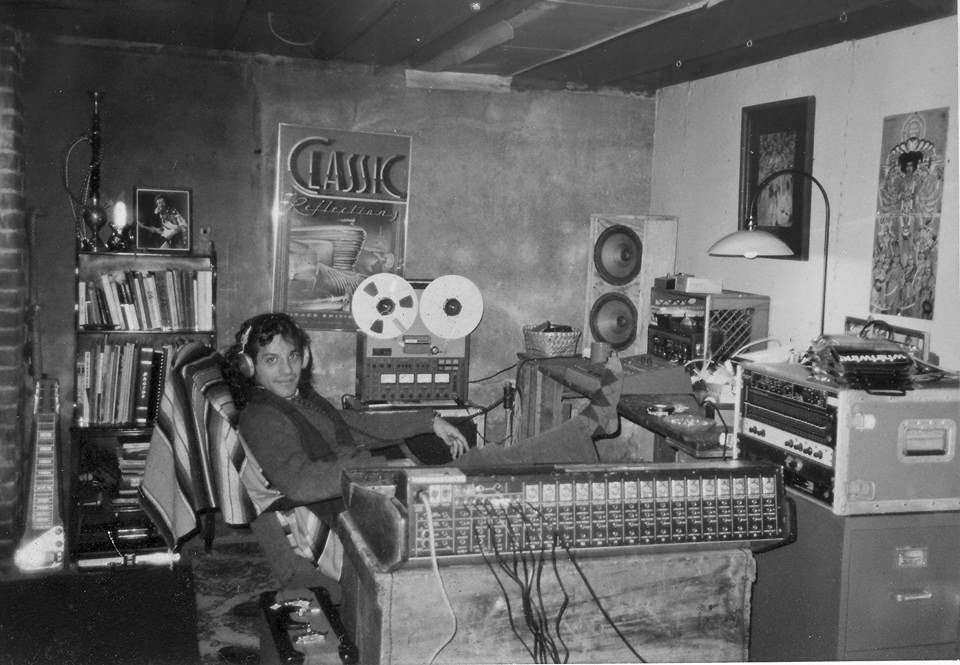

Our engineer was Fritz Richmond, who was a former member of the Jim Kweskin Jug Band and still played with Maria Muldaur. He was one of the bright lights of the Greenwich Village folk scene of the late '50s/early '60s. We didn't know who he was until years later. I could go on and on about Fritz.

Fritz Richmond with Maria Muldaur and Jim Kweskin Jug Band

Often during the making of "That's Right," it was just Fritz and I alone in the control room. We cut the guitars direct, straight into the board, no amp involved. I was frustrated by all the little clicky noises the guitars made.

"I hate recording!" I said.

"Recording is FUN!" Fritz says.

That's the kind of guy he was. Sometimes, he would show up wearing funny hats, bowlers, and tam-o'-shanters. And he was a calming presence, like a great pediatrician.

I ended up stuffing a bunch of toilet paper down at the first fret, and that cut out most of the noises. Later, when I could hear what compression was, I realized that Fritz had really whomped down on those guitars. That's why they sound like a record.

For a great example of what compression sounds like, listen to the guitars on the Beatles' "Baby You Can Drive My Car."

The clap sound on the LINN DRUM was a weak little KACK. Nothing like the big disco clap on ZAPP! Records. We fooled with that for a while. Fritz put a tight delay on it, maybe 22 milliseconds, and turned up the feedback so there were three or four repeats, so instead of KACK, we had the very satisfying THRAPP we all know and love.

Then we recorded vocals. The backup singers were Valerie, her sister Shannon, and Lori Lamphear, a 1980 NUSHOOZ alumnus. We were meticulous about the pronunciation of certain words. We spent hours and hours on this. A good example is how they swallow the 'T' on the word 'WAIT.'

Another feature of the vocals is the quarter note delay on Valerie, which gives the lead vocal a psychedelic dreaminess even if you don't notice it right away. The syncopated vocal lends itself to a straight delay time, whereas a less syncopated line would suggest a dotted 8th note delay.

After all that work, the track still sat there. Then I was listening to Jungle Love by The Time. That track had some bottles for percussion. I came up with a stereo bottle part and a stereo tambourine part, and then the track really started to roil and boil. It was the final touch…almost.

THE REMIX

The sample at the beginning of the I.C.W. 12" [which we affectionately call "the Barking Seal"] was played by Dutch D.J. Peter Slaghuis on an EMU EMULATOR II. The model II still used those big 3" floppies, like a Commodore 64. Over the years, people have told me what the sample was, but I can never remember.

He achieved the stutter effects [I-I-I-Can't Wait] by actual tape-cutting with a razor blade and editing block. I watched him cutting tape at Atlantic Studios in NYC. He had some good tricks, but he was very shy, didn't speak very good English, and didn't like people around when he worked.

So…

That's all the technical musical hardware and anthropology that I can recall. It's amazing that people are still interested in this song forty-plus years on. You can see what a bare-bones process it was, And what a miracle it is. Thanks for the letter.

John R. Smith

NUSHOOZ

11.28.23

P.S. Forty years later, we learned that Peter Slaghuis, who did the famous ‘Dutch Remix’, didn’t like the song, so he didn’t fool with it very much. His dream was to do remixes for ABBA…which is about as far away from Nu Shooz as you can get!

CHOONS: FROM PORTLAND TO THE WORLD; The Story of Nu Shooz' "I Can't Wait."

Host Diego Martinez from CHOONS takes us back to the Mid-70s and the incredible series of events that led to “The Bassline Heard’ Round the World.” It’s one of our favorite interviews ever. Enjoy!

CHOONS is a podcast about "The Songs we vibe to," dedicated to the "History and longevity of underrated and much loved tunes."

Host Diego Martinez takes us back to the Mid-70s and the incredible series of events that led to "The Bassline Heard 'Round the World." It’s one of our favorite interviews ever. Enjoy!

Nu Shooz and director Jim Blashfield talk about “I Can’t Wait” in an interview w/Sloan de Forest

When citing examples of music video directors with signature looks, names like Anton Corbijn or Matt Mahurin jump out, but the unfortunately overlooked genius in this club must be Jim Blashfield. Creating a trademark visual sensibility with just a handful of videos, the Oregon native created dreamlike fantasies with a cut-out xerographic animation style that reveals a gentle magic hiding the ordinary — strangely devilish garage-sale travelogues, if you will. Jim’s artisan videos, which embrace both texture and perspective, include Talking Heads’ “And She Was,” Paul Simon’s “Boy in the Bubble,” Tears for Fears’ “Sowing the Seeds of Love” and Michael Jackson’s wildly self-effacing “Leave Me Alone.” His most visually-trippy grab bag of kitchen sink mischief, though, is his clip for Nu Shooz’s “I Can’t Wait” from their album Poolside. The video he created for his fellow Portlanders, Valerie Day and John Smith, helped propel the duo’s inescapably catchy hit into pop history — and also into the still-curious minds of video music fans everywhere.

I spoke to Jim recently about his career, and he shared his experience on creating this amazing piece of filmmaking:

When citing examples of music video directors with signature looks, names like Anton Corbijn or Matt Mahurin jump out, but the unfortunately overlooked genius in this club must be Jim Blashfield. Creating a trademark visual sensibility with just a handful of videos, the Oregon native created dreamlike fantasies with a cut-out xerographic animation style that reveals a gentle magic hiding the ordinary — strangely devilish garage-sale travelogues, if you will. Jim’s artisan videos, which embrace both texture and perspective, include Talking Heads’ “And She Was,” Paul Simon’s “Boy in the Bubble,” Tears for Fears’ “Sowing the Seeds of Love” and Michael Jackson’s wildly self-effacing “Leave Me Alone.” His most visually-trippy grab bag of kitchen sink mischief, though, is his clip for Nu Shooz’s “I Can’t Wait” from their album Poolside. The video he created for his fellow Portlanders, Valerie Day and John Smith, helped propel the duo’s inescapably catchy hit into pop history — and also into the still-curious minds of video music fans everywhere.

I spoke to Jim recently about his career, and he shared his experience on creating this amazing piece of filmmaking:

“I explained that I wanted to improvise it. I didn’t want to plan it at all. I wanted the experience of just making it up from what was around when we got to the studio. The morning of the shoot, I loaded my kitchen table and chair and lamp into my car along with some biology slides and a coffee maker and some kind of cigar box and headed over to the stage. I rummaged around among the props there and found some canvas and some walls from a commercial and some fake cactuses. I went upstairs where the band and the crew were assembled– we had a good and very professional crew, as you can tell from looking at the images– and told them I would be back in 10 minutes with instructions about setting up for the first shot, about which I had no idea whatsoever. I rummaged around in people’s offices and borrowed a few other items which looked promising. I went upstairs and said we were doing a video that took place in the desert, and set people about creating that. It seemed like we needed something in front of the green walls, so the video editor went down the street and came back with a dumpster, and rigged a way to make the lid go up and down with fishing line. I recalled that my friends who were on vacation had a great looking dog house for their dog Buster, and some people went there and stole it. We called up a friend with an obedient dog who would stay when asked, and he brought his pooch over. Somebody else got a bunch of tools out of the trunk of their car.”

“After the shoot the next step was a trip to Seattle to get the footage transferred and do strange things to some of it. Then, for post production, a trip to the thrift store and the corner grocery, returning with every other little gadget and doo-dah you see on the screen. The video editor was Mike Quinn who subsequently did the high-degree-of-difficulty video editing for my videos for Paul Simon, Peter Gabriel and others. During editing I called my friend Roger Kukes, the animator, and asked him if I could use part of his animated film ‘Up’ for the ending of the video where Valerie opens the little box and all the wiggly images come out, revealing all knowledge known to humankind. I recall that the opening scene with the Banana and souvenir totem pole dropping onto a piece of metal with holes in it took about 8 hours to composite, and was completed while I slept on the couch in the editing room. The scene where the image of the dog watching the golf ballish thing swings in and unceremoniously lands on Valerie’s head– and where it remains for longer than might be considered, strictly speaking, necessary– is there because it made me laugh when we tried it in post and was left in because nobody said I couldn’t. We had a take in which the guy with the smoke machine walks through in the background waving it around while Valerie is singing, but I left that out, due to some conservative impulse on my part, which I regret.”

Exclusively for The Golden Age of Music Video, Valerie Day and John Smith collectively answered a few questions about the video by email:

Q: How did you and Jim find each other?

A: Jim Blashfield was a local film maker/artist working in our hometown, Portland Oregon. We knew him first as a cartoonist, His drawings appeared in the local ‘free press.’ By the time the Shooz signed to Atlantic he’d become a world class video director, and his stuff was unique. It seemed like a good fit, and as it turned out, it was. His ‘I Can’t Wait’ video is our favorite of the three we made.

Q: How was working with Jim during the shoot? He said you really went with the flow.

A: The whole shoot was a swirl of madness. We had 48 hours between coming off the road and a vacation in Mexico. Jim improvised the whole thing, grabbing up objects like plastic sharks and samovars and somehow working them into the shoot.

Q: What do you recall as a highlight from the shoot?

A: A few days ago we were talking to a friend who worked on that shoot. She says she remembered Valerie sitting on a chair atop a spinning platform. They shot hours of this spinning thing. Jim kept saying ‘Shoot it one more time.’ None of that footage made the final cut.

Q: After I spoke to Jim, I realized that most of it was done on the fly and there’s no real subtext, other than Valerie plays a scientist examining things and trying get the answer to “tell me what it’s all about”. When people ask you to explain parts of the video, do you find that irksome or amusing?

A: We prefer to let people come up with their own interpretation. Carl Jung’s work with the unconscious suggests that everything in our heads is connected, all our preferences and prejudices, what we like and what we don’t. Somehow the random imagery in the “I Can’t Wait” video ended up saying exactly what we wanted it to say.

Q: Jim said, “If viewers look closely they may notice that happiness seems to be represented as a shark found lurking in a coffee pot, a metaphor which is certainly worth considering, if you ask me.” What do you think about that?

A: In the hands of a lesser director we might have ended up with a melancholy/needy girl waiting by the phone. Not Jim. It wasn’t that we discussed our vision so much as he was just as psychedelic as we were.

Q: What did you think the first time you saw it, and what do you think when you see it now?

A: MTV was a cultural revolution. In some ways it ruined music, in some ways it added a new dimension. At the time it was just thrilling to be a part of it, to know they were watching us in Cleveland…and Brazil. When we see it now, it still holds up as a perfect piece of art, one that represents Nu Shooz exactly how we wanted it to be seen.

I Can’t Wait: The Video…What IS It All About?

Since it first appeared in 1986 during the heyday of MTV, people having been asking us about the video for “I Can’t Wait”. What is the meaning behind it all? Why is Valerie pulling a shark out of a coffee pot? Is the dog wearing sunglasses a part of the band?

Since it first appeared in 1986 during the heyday of MTV, people have been asking us about the video for “I Can’t Wait”. What is the meaning behind it all? Why is Valerie pulling a shark out of a coffee pot? Is the dog wearing sunglasses a part of the band?

John and I have always loved the video for I Can’t Wait. Working on it with Jim Blashfield was one of the highlights of our pop music career. Jim lives in Portland with his wife, Mellisa Marsland (who also produced the video), and his daughter Hallie. We have gotten to be good friends with Jim and his family over the years. We even got to work with Jim recently on a multi-media performance called Brain Chemistry For Lovers. Jim directed, edited the script, and created video for it. Over the years, we’ve had a few discussions about the music business and assorted other music-related topics, but because the video for ICW had always “made sense” on a non-literal level to us, John and I had never thought to ask Jim, “What was that all about?”

Enter Sloan de Forest, a woman who calls herself “the Pauline Kael of classic MTV.” Sloan had a blog called “Images of Heaven: Remembering The Lost Art of Music Video.” She had decided it was time to uncover the story behind the “making of” ICW. She emailed Jim. He responded and copied us on the email. The blog no longer exists, but Jim's response does. Here it is in its entirety:

The video came about because I was a filmmaker living in Portland and my producer Melissa Marsland and I had just finished our first video, And She Was, and another for Joni Mitchell called Good Friends, and our fellow Portlanders-- the Nu Shooz crew who had been having some big international dance hits-- asked us to do a video for them. I explained that I wanted to improvise it. I didn't want to plan it at all. I wanted the experience of just making it up from what was around when we got to the studio. The morning of the shoot, I loaded my kitchen table and chair, and lamp into my car, along with some biology slides and a coffee maker, and some kind of cigar box, and headed over to the stage.

I rummaged around among the props there and found some canvas and some walls from a commercial, and some fake cactuses. I went upstairs, where the band and the crew were assembled-- we had a good and very professional crew, as you can tell from looking at the images-- and told them I would be back in 10 minutes with instructions about setting up for the first shot, about which I had no idea whatsoever. I rummaged around in people's offices and borrowed a few other items which looked promising. I went upstairs and said we were doing a video that took place in the desert and set people about creating that. It seemed like we needed something in front of the green walls, so the video editor went down the street and came back with a dumpster and rigged a way to make the lid go up and down with fishing line.

I recalled that my friends who were on vacation had a great-looking dog house for their dog Buster and some people went there and stole it. We called up a friend with an obedient dog who would stay when asked, and he brought his pooch over. Somebody else got a bunch of tools out of the trunk of their car. Now, fully prepared, with the band members doing an admirable job of hiding their apprehension, we were all set to shoot the live-action! Valerie was completely along for the ride with a great sense of playfulness, as her song was absolutely misinterpreted.

After the shoot, the next step was a trip to Seattle to get the footage transferred and do strange things to some of it, and then, for post-production, a trip to the thrift store and the corner grocery, returning with every other little gadget and doo-dah you see on the screen.

The video editor was Mike Quinn, who subsequently did the high-degree-of-difficulty video editing for my videos for Paul Simon, Peter Gabriel, and others. During editing, I called my friend Roger Kukes, the animator, and asked him if I could use part of his animated film Up for the ending of the video where Valerie Day opens the little box, and all the wiggly images come out, revealing all knowledge known to humankind.

I recall that the opening scene with the Banana and souvenir totem pole dropping onto a piece of metal with holes in it took about 8 hours to composite and was completed while I slept on the couch in the editing room. The scene where the image of the dog watching the golf ballish thing swings in and unceremoniously lands on Valerie's head-- and where it remains for longer than might be considered, strictly speaking, necessary-- is there because it made me laugh when we tried it in post and was left in because nobody said I couldn't. We had a take in which the guy with the smoke machine walks through in the background, waving it around while Valerie is singing, but I left that out due to some conservative impulse on my part, which I regret.

When they saw the video, the record company called it "unusual," or perhaps "quite unusual," or maybe "very unusual," or possibly some other less neutral phrase that I have repressed.

So what is it? Besides being a promo for a band and a song, it is an experiment to see what results when you take a line from the video "tell me what it's all about" and decide that Valerie is some kind of a scientist with an interest in small appliance repair instead of somebody waiting, lovesick, for a phone call, and let everything follow logically from that. If viewers look closely, they may notice that happiness seems to be represented as a shark found lurking in a coffee pot, a metaphor which is certainly worth considering if you ask me.

This being Portland and Nu Shooz being Nu Shooz and me being something of a troublemaker with a perhaps overdeveloped allegiance to the ordinary, the Portland MTV video premiere party was held in a truck-stop cafe and bar up the street. The local news sent a mobile truck to broadcast the glamorous event live.

By the way, and not incidentally, Valerie Day and John Smith, the Nu Shooz core, are fabulous and very versatile musicians and have a new CD out, Pandora's Box, that is exquisitely produced, hypnotically beautiful and completely different from the zillion seller Poolside, of which I Can't Wait was a part. I didn't have in mind to promote their CD when I began this fascinating run-on mind-evacuation, but since I'm talking about it... https://nushoozorchestra.bandcamp.com/album/pandoras-box

So hey, thanks for your interest, Sloan. I agree that some pretty interesting work was made during that period, and am aware that my co-conspirators and I were behind a few of the more interesting ones. That was our intention. To do stuff that bent the expected trajectory or looked deeper, or cast light and attention on subjects, images, and ways of seeing things that were often overlooked. Thanks for appreciating that!

I must go now and milk the swan.

Jim Blashfield

Reading Jim’s account of how the video came together made us appreciate him even more than we already do. And what a blast to have his version of the making of! He’s a master at using images to explore that theme park of the mind – the unconscious – and give us all a great time while doing it.

Thought I’d share it with you.

- Valerie

![Welcome to your summer. Yes, it's finally here! And it's the 46th anniversary of the very first NuShooz gig. [Colonel Summer's Park, Portland, Oregon, June 21st, 1979.] What a different world that was; pre-internet, no smartphones or smart toasters,](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54cee645e4b01fa0f0bfc5f9/1750512289030-8M6PFU9H9F6KHZ2HFJ94/image-asset.jpeg)