Everything About The Making Of I Can't Wait

Did you know 'I Can't Wait' was originally much faster? When we slowed it down to 104 BPM in the studio, the band thought John was crazy! But that slower groove, combined with some engineering magic and creative percussion (including wine bottles!), helped create the sound y’all know and love.

The most frequently asked FAN QUESTIONS are about the making of “I Can’t Wait.” So, here’s an attempt to include every technical detail about how we made that song forty-one years ago. It’s amazing that we’re still talking about it almost half a century later!

The recording of “I Can’t Wait” perfectly captures that unique moment in music history when analog and digital technologies were colliding. Looking back, it’s amazing how we managed to create such a rich, layered sound with relatively simple equipment. Every decision - from the LINN drum machine to engineer Fritz’s compression techniques - helped shape what would become Nu Shooz’s signature hit.

Subject: I Can't Wait production

Message: Hello Valerie and John! I was listening to "I Can't Wait" today and would love to know how the song was produced. Equipment. Instruments. Etc... Has this information ever been shared in an interview somewhere that I can look up? Thanks for this wonderful classic. — Patrick

Hi Patrick!

Thanks for your letter. We get asked this question a lot, so I'm going to write down the definitive version of THE MAKING OF 'I CAN'T WAIT.'

EVERYTHING ABOUT THE MAKING OF NU SHOOZ 'I CAN'T WAIT' (That we can remember.)

It was the winter of 1983, a time almost unrecognizable now. TV still signed off at 2 a.m. Cable was just getting started. And none of the gear existed that we take for granted now. MIDI was new and prohibitively expensive. NU SHOOZ had a horn section but no keyboards.

Without MIDI or a multitrack, it was harder to write songs, to make them stand up and walk around by themselves. We were playing all the time, almost every weekend, and this created an insatiable need for new material. People would leave the band and you couldn't play this or that song anymore. The new guy would come in, and we'd have to teach him all the moldy oldies. There were songs I was so tired of that it hurt to play them. And in Portland, funk records were hard to find. So, I had to become a full-time songwriter. In the Brill Building days, writers like Carole King and Jerry Goffin made hit songs by putting in the hours—showing up every day.

I started writing songs in batches of ten. How it worked was, I'd number one to ten on a piece of paper and then slot in a bunch of tempos, like this:

Mid-tempo [meaning funk]

Mid-tempo

Fast

Mid-tempo

Slow

Fast... etc

Next, I would assign a Kick/Snare pattern to each number. When you're writing songs, specifically Funk songs, you become a connoisseur and collector of Kick/Snare patterns. Some of my personal favorites are Surf Beats for fast stuff, and anything by Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis for the FUNK.

I got a lot of Nu Shooz Kick/Snare patterns from the Grandmaster Flash album 'THE MESSAGE.'

I tried to finish two songs a week for Wednesday rehearsal. I.C.W. was one of the first songs to come out of this batch writing process.

As I said before, it was hard without any gear to make a song hang together in your head. My Mother-in-Law had this thing called an OMNICHORD. It looked sort of like a zither, but it was completely electronic. It had a little drum machine in it, you know, like those old 'Home Organ' beats: Swing, Waltz, Bossa Nova, etc. And there was one called ROCK BEAT 1.

I plugged the OMNICHORD into a cassette machine and recorded ROCK BEAT 1 at a bunch of different speeds. This worked for all the tempos mentioned above. This was a vast improvement. Before that, I was trying to make drum beats by banging on a kitchen table with dinner plates on it.

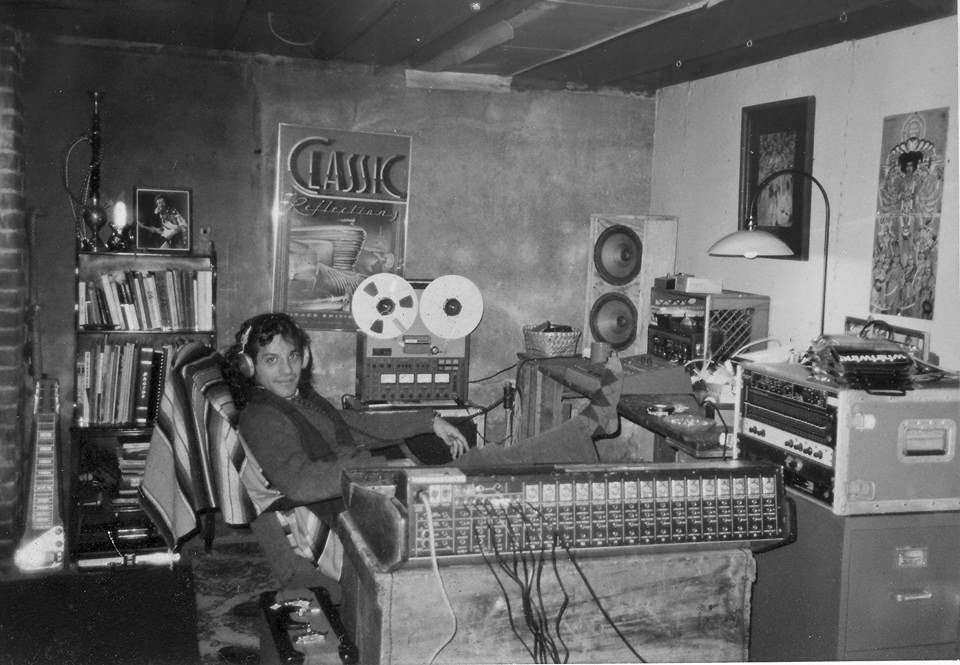

Then I begged our manager to rent a ¼" four-track machine from the local sound company. For the princely sum of $24 a month, they rented us a TEAC 3440. Great machine. [I still have it, by the way.] Right away, I filled a tape with my OMNICHORD beats, and just like that, I was in business. Writing songs was suddenly so much easier.

I.C.W. was written while sitting on a wooden stool next to the furnace in our basement rehearsal space. The bass line was composed on a 1965 Fender P-Bass [Black/Rosewood Fretboard/Tortoiseshell guard] belonging to our Soundman. The Bass was tuned to Drop-D. The chords were played on a cheap [but nice] nylon string guitar called a DISCOTECA SERRANO.

I mixed the demo to cassette, put it in my Walkman, and spent the next month or so walking around and around the block. The first chorus bit that I heard in my head was:

"I Can't Wait till FRIDAY NIGHT"

Eventually, that morphed into the call-and-response:

'Cause I Can't Wait

BABY

I CAN'T WAIT.

Phew!

So now that the chorus was "sitting still," the song needed verses.

My love— The first two words of a Lionel Richie song

Tell me what it's all about— A line from my Bone Pile

You've got something

That I can't live without— A vague come-on

Happiness— The first word in an Alan Toussaint song

Is so hard to find— My answer to his line

Etc., etc.

Back then, I was good at one-and-a-half verses.

Anyway…

We had a Wednesday rehearsal coming up, and I didn't have anything but this half-finished song. The band was actually loading their gear into the basement. Valerie was standing at the sink, and I was at the kitchen table. In ten minutes, I wrote the rest of the song. There! I shoved the paper at Valerie.

She said, "Good enough."

There was just enough time left to scribble up a horn chart.

So now it's 1984, and we're playing I.C.W. in the clubs. We called it a B-level dance song. People danced to it, but we played it way too fast, just to get it over with. Around that time, Rick, our manager, called.

"We need to record something. I need something to market."

He didn't like our first album, "Can't Turn It Off," and he was right. It didn't represent the band anymore. Rick had just inherited five grand from a deceased aunt, and he wanted to bankroll a Nu Shooz album.

He asked me, "Do you have any songs you like?"

"Well," I said, "the one that sounds the most real is 'I Can't Wait.'"

By real, I meant that it sounded the most like a real record. Valerie sounded great on it right away. [Her voice worked perfectly an octave above my songwriter croak.]

Rick booked us into Cascade Studio in Portland, Oregon. Sessions began in the summer of 1984. Before we went into the studio, I was pondering whether or not to use a drum machine. We used to make fun of the early ones. The ROLAND 808 only became popular with the advent of Hip-Hop. We tried cutting the song with a live drummer first, and that just didn't work. We had to have that machine kick/snare/clap…like ZAPP!

For a band that couldn't afford keyboards, a drum machine was out of the question.

Fortunately…

We knew a rich guy who didn't play but had a house full of all the best gear.

He owned a LINN LM-1.

The LINN LM-1 was Roger Linn's first commercially available drum machine. It was so much heavier sounding than an 808. It retailed for $5,000 [in '80s money!]

Next, we put on a bass.

Live bass didn't cut it, either. So we hired a bass player, Nate Philips, who owned a MINI-MOOG. He was one of the great Portland funk players, going back to the '70s band Pleasure. Nate dialed in the sound and played the part. I got my own MINI-MOOG not long after that, but I never could get close to the sound that he made.

The piano was a seven-foot Steinway.

The guitars were a cream-white [nicotine yellow] 1969 Fender Stratocaster and my number one fave 1967 Gibson 335 [battered black].

This is it — John’s 1967 Gibson ES335.

The horns are real, just trumpet and tenor doubled.

Our saxophone player, Dan Schauffler, had just bought a ROLAND JX-3P synth. It had eight preset sounds, and I'm pretty sure we used them all. A good example is the chime in the intro, which was kind of a take-off on "Tubular Bells" by Mike Oldfield, and the legato synth string line that follows. The JX-3P was one of the first commercially available MIDI synths. Everything was new back then.

The Roland JX-3P in all it’s magnificence.

Cascade Studio had a two-inch 16-track machine, which was and is kind of rare, then and now.

It was a real stroke of luck for two reasons. First of all, the tracks are wider than a 2" 24-track, and they actually have a fatter sound. And second, we didn't have those eight extra tracks to clutter up the song.

Before we had anything on tape, I had an epiphany and realized that it would be so much funkier if we slowed it down. I tramped around the studio parking lot, singing the bassline, feeling for where the funky place was. Then I ran back into the control room. We slowed it down to 104 bpm from however the hell fast we were used to playing it.

The band thought I was NUTS!

Especially Valerie, who found it impossible to sing over.

As history shows, we worked that out.

Our engineer was Fritz Richmond, who was a former member of the Jim Kweskin Jug Band and still played with Maria Muldaur. He was one of the bright lights of the Greenwich Village folk scene of the late '50s/early '60s. We didn't know who he was until years later. I could go on and on about Fritz.

Fritz Richmond with Maria Muldaur and Jim Kweskin Jug Band

Often during the making of "That's Right," it was just Fritz and I alone in the control room. We cut the guitars direct, straight into the board, no amp involved. I was frustrated by all the little clicky noises the guitars made.

"I hate recording!" I said.

"Recording is FUN!" Fritz says.

That's the kind of guy he was. Sometimes, he would show up wearing funny hats, bowlers, and tam-o'-shanters. And he was a calming presence, like a great pediatrician.

I ended up stuffing a bunch of toilet paper down at the first fret, and that cut out most of the noises. Later, when I could hear what compression was, I realized that Fritz had really whomped down on those guitars. That's why they sound like a record.

For a great example of what compression sounds like, listen to the guitars on the Beatles' "Baby You Can Drive My Car."

The clap sound on the LINN DRUM was a weak little KACK. Nothing like the big disco clap on ZAPP! Records. We fooled with that for a while. Fritz put a tight delay on it, maybe 22 milliseconds, and turned up the feedback so there were three or four repeats, so instead of KACK, we had the very satisfying THRAPP we all know and love.

Then we recorded vocals. The backup singers were Valerie, her sister Shannon, and Lori Lamphear, a 1980 NUSHOOZ alumnus. We were meticulous about the pronunciation of certain words. We spent hours and hours on this. A good example is how they swallow the 'T' on the word 'WAIT.'

Another feature of the vocals is the quarter note delay on Valerie, which gives the lead vocal a psychedelic dreaminess even if you don't notice it right away. The syncopated vocal lends itself to a straight delay time, whereas a less syncopated line would suggest a dotted 8th note delay.

After all that work, the track still sat there. Then I was listening to Jungle Love by The Time. That track had some bottles for percussion. I came up with a stereo bottle part and a stereo tambourine part, and then the track really started to roil and boil. It was the final touch…almost.

THE REMIX

The sample at the beginning of the I.C.W. 12" [which we affectionately call "the Barking Seal"] was played by Dutch D.J. Peter Slaghuis on an EMU EMULATOR II. The model II still used those big 3" floppies, like a Commodore 64. Over the years, people have told me what the sample was, but I can never remember.

He achieved the stutter effects [I-I-I-Can't Wait] by actual tape-cutting with a razor blade and editing block. I watched him cutting tape at Atlantic Studios in NYC. He had some good tricks, but he was very shy, didn't speak very good English, and didn't like people around when he worked.

So…

That's all the technical musical hardware and anthropology that I can recall. It's amazing that people are still interested in this song forty-plus years on. You can see what a bare-bones process it was, And what a miracle it is. Thanks for the letter.

John R. Smith

NUSHOOZ

11.28.23

P.S. Forty years later, we learned that Peter Slaghuis, who did the famous ‘Dutch Remix’, didn’t like the song, so he didn’t fool with it very much. His dream was to do remixes for ABBA…which is about as far away from Nu Shooz as you can get!

Fan Questions: Tales from the Studio - Remember Those Analog Days?

What do granny glasses, pet rabbits, and wonky cassette players have in common? They're all part of our adventures in the analog recording world. Get ready for some studio stories that'll make you grateful for digital.

Dear NU SHOOZ, can you talk about some difficult recording studio experiences?

Anthony

Tampa, FL

Hi there, Anthony,

You asked about difficult recording experiences. So here's a few.

1. This doesn't come under the category of 'difficult,' but it was formative. When we recorded the original 'American' mix of "I Can't Wait," the audio engineer Fritz Richmond said, "Is this going to be a single?"

And we were like, "Single? What's that?"

He ended up cutting the intros and verses and "middle-8s" in half and made some breakdowns without which the famous version of "ICW" wouldn't have been possible. He did this by cutting up the 2" master tape with a razor blade on an editing block. There was no digital audio back then, and that's how it was done.

Fritz Richmond was this incredible, super-humble guy. You'd never know he was part of the Greenwich Village folk scene and actually started the whole 'granny glasses' thing. He never brought any of that up while we were recording - that's just the kind of person he was.

He’s deserving of a whole blog post of his own. Someday soon, we’ll write it.

Fritz with his washtub bass and granny glasses.

2. We were down in L.A. at Sunset Sound Factory recording "Should I Say Yes." We couldn't get a vocal take that I liked better than the demo. Eventually we decided to use the vocal from the demo tape. The problem was, the demo vocal was on 1/4" four track and the master was 2" 24 track. Also, they were running at slightly different speeds. And there was no time code. So we had the demo FedExed down from Portland, set up a machine and 'flew in' the vocal one phrase at a time. To do this Jeff Lorber marked a place on the demo tape with a grease pencil, played the master and hit go on the other machine. It would take several attempts before it landed in the right place. We did the whole song like that.

Sunset Sound Factory

Jeff Lorber

3. At some point in the making of a record, we'd have to make a cassette and take it in to the A&R department at the Label. The problem was, the people at the label always had the crappiest stereos, and no two cassette players ran at the same speed. This was way before CDs or DATs. So we're sitting with whoever and the tape is either running too slow or too fast, quaaludes or helium, and everything sounds stupid.

image by Feodor Chistyakov

There you go. Thanks for the question. There are so many more. Like the all-nighter I pulled for a band I was producing. Next day, I found out it was the wrong tune!

Like the pet rabbit, Gary who liked to chew on the cables and eventually died for his bad lifestyle choices.

All the best,

John R. Smith

Nu Shooz

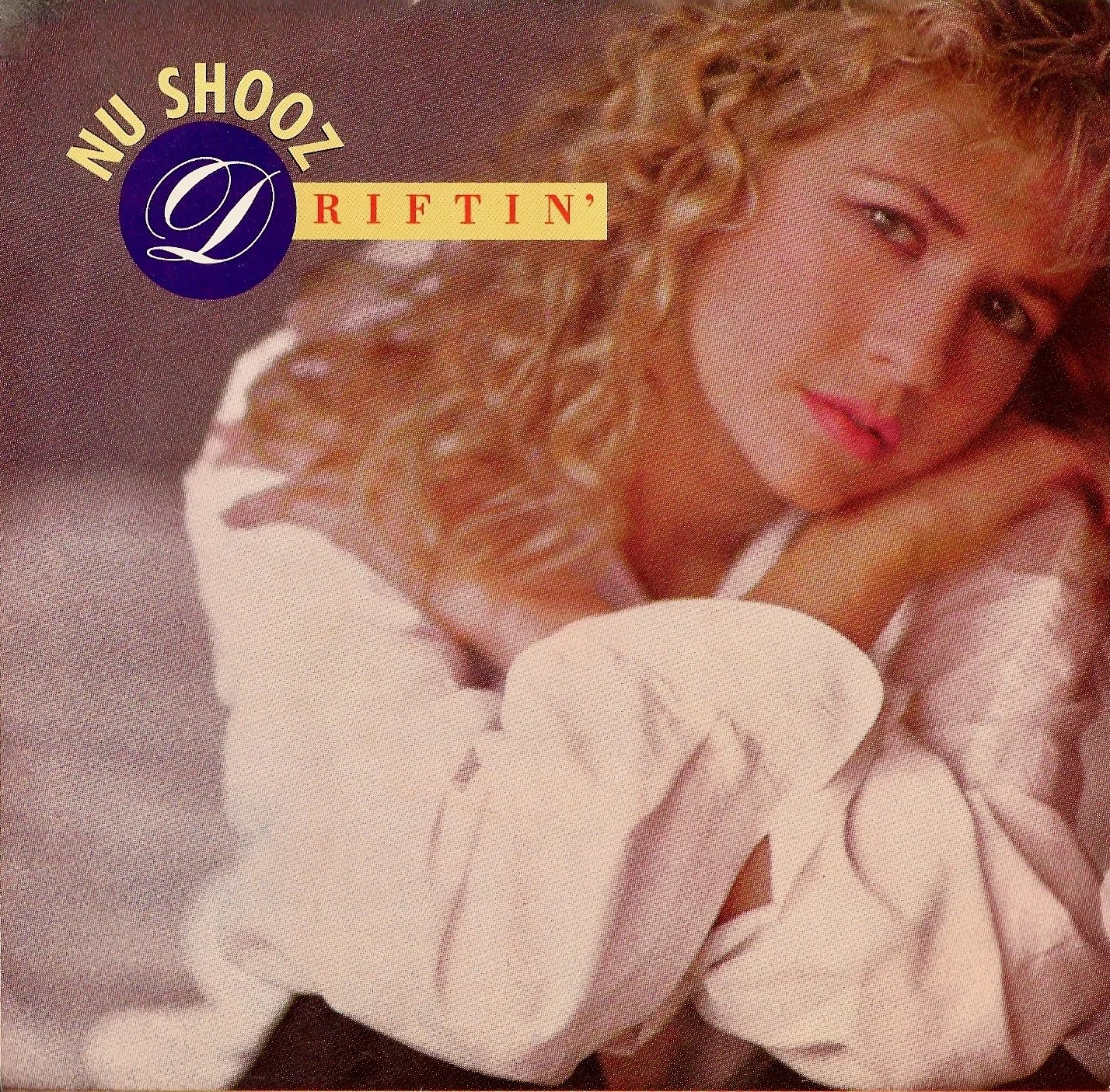

Stealing Like an Artist: The Creation Story of Driftin’

Dive into the creative process behind Nu Shooz's 'Driftin,' an 80s song that embodies Austin Kleon's philosophy of artistic influence and transformation.

In 2012, Austin Kleon wrote an influential little book called ‘Steal Like an Artist.’ “What a good artist understands is that nothing comes from nowhere. All creative work builds on what came before. Nothing is completely original.”

The Nu Shooz song ‘Driftin’ is a perfect example of this kind of thinking in action. The song was written in 1987 for the Shooz’s second Atlantic album ‘Told U So.’ My songs usually start with a nice set of chords. ‘Driftin’ was based on two chords one of my friends used to play. I often name music bits: the BB King Lick, the Watchtower Progression, the Stevie Wonder Thing, etc. So the first two chords in Driftin’ are the Azul Chords, named after my late friend and fellow songwriter, Azul Amey.

The harmony (on the word Driftin’) came from some R&B tune I can’t even remember. I just knew I could use that bit for something. And it was that tiny piece that put the song into the Ballad box. Lastly, there was a Jimi Hendrix song called ‘Driftin’ on his album ‘Cry of Love.’ I can’t remember how that piece of DNA drifted into the songwriting process, but that one word fit everything else that was going on…

I remember exactly where I was sitting when this was all coming together. It was late spring. I had a cute little Gibson B-25 on my lap. I’m playing the chords and trying to stuff every nautical oceanic seafaring thing into the lyrics. And during this whole process something happened that was more than stealing. It’s more like borrowing a few lumps of clay from fellow artists, taking it back to the potter’s wheel, spinning and kneading it till it becomes something completely new. My version of Driftin’ bears no resemblance to Jimi’s, but he was definitely along for the ride.

We loved this song so much that we recorded it twice: first in 1987 on our album ‘Told U So’ and then in 2010 on ‘Pandora’s Box.’

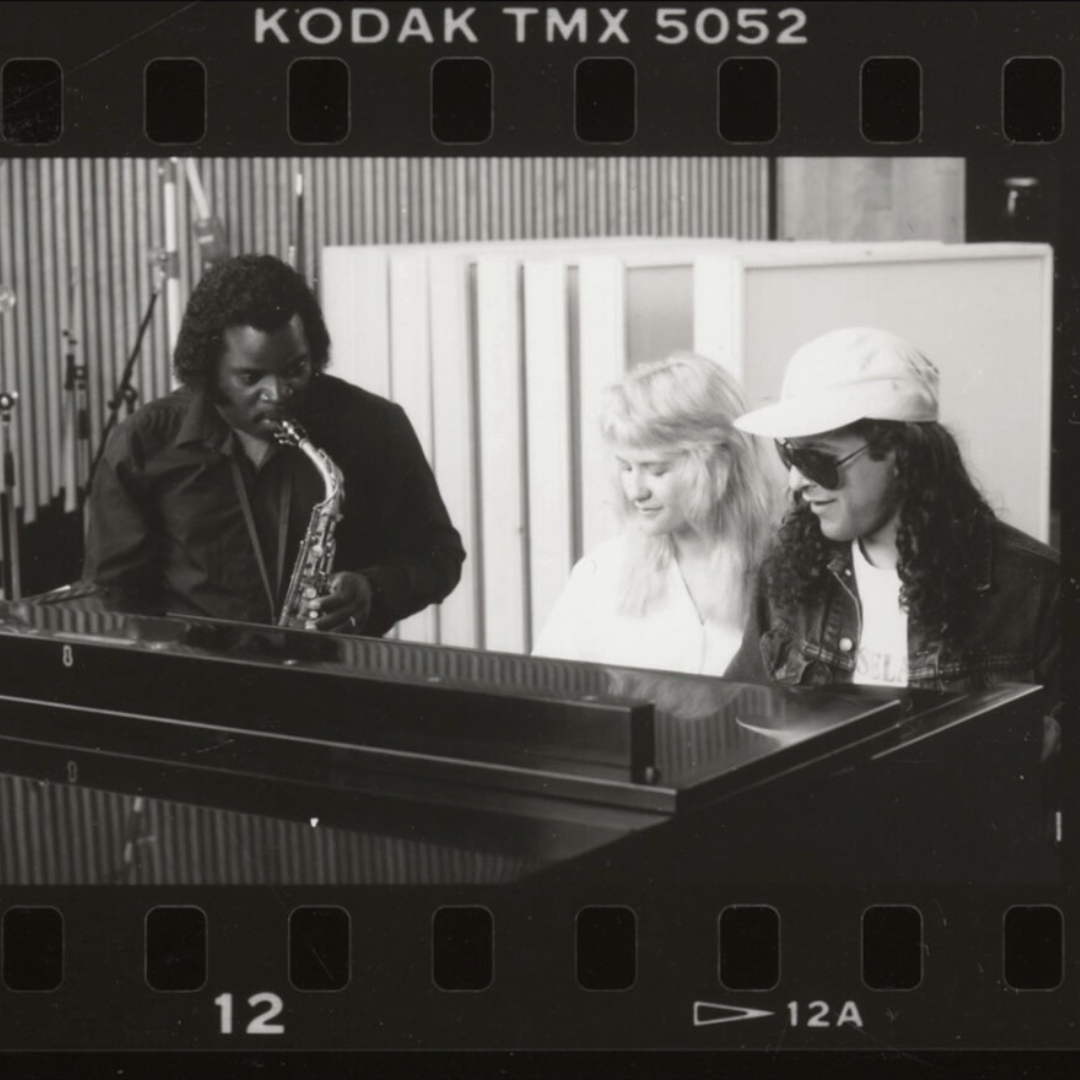

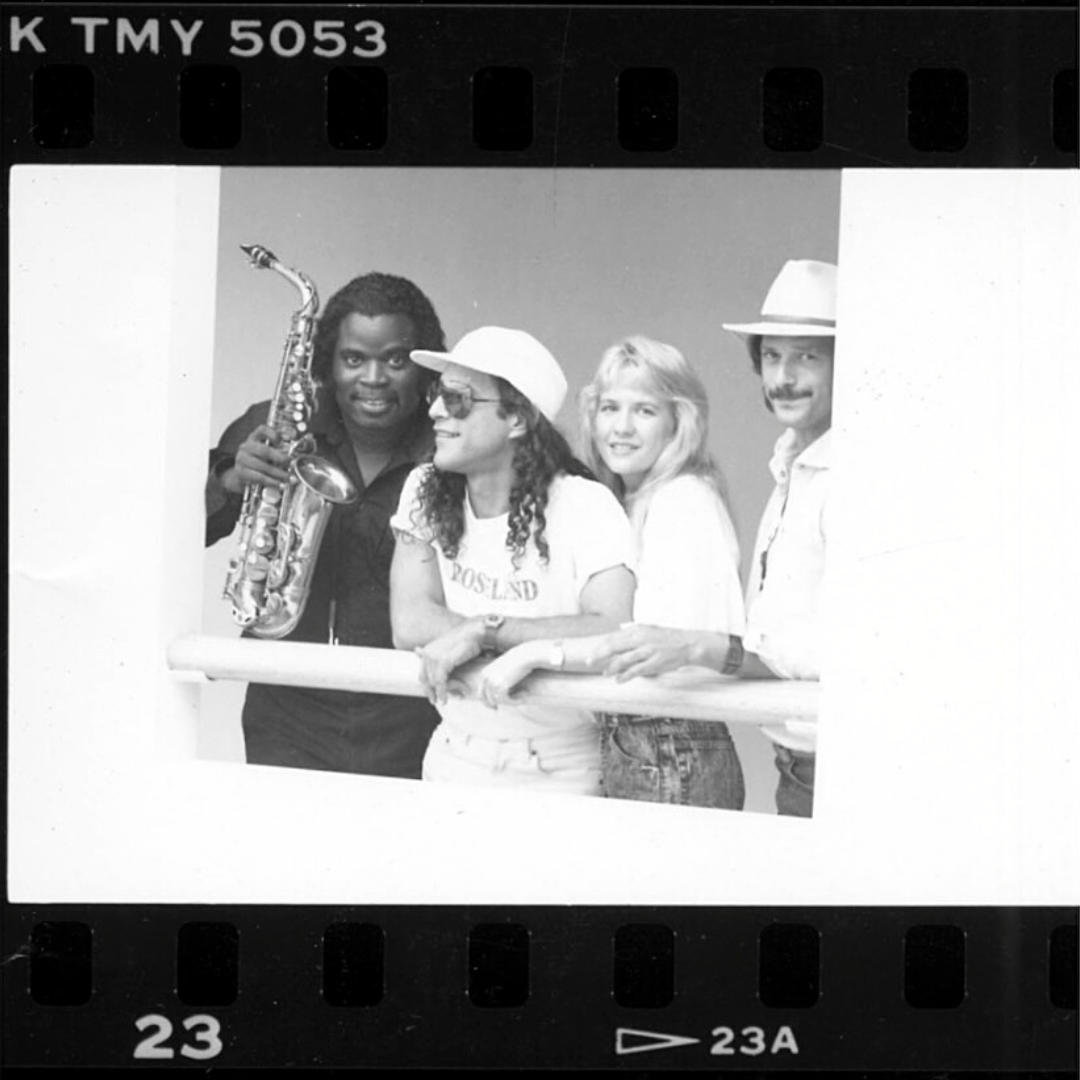

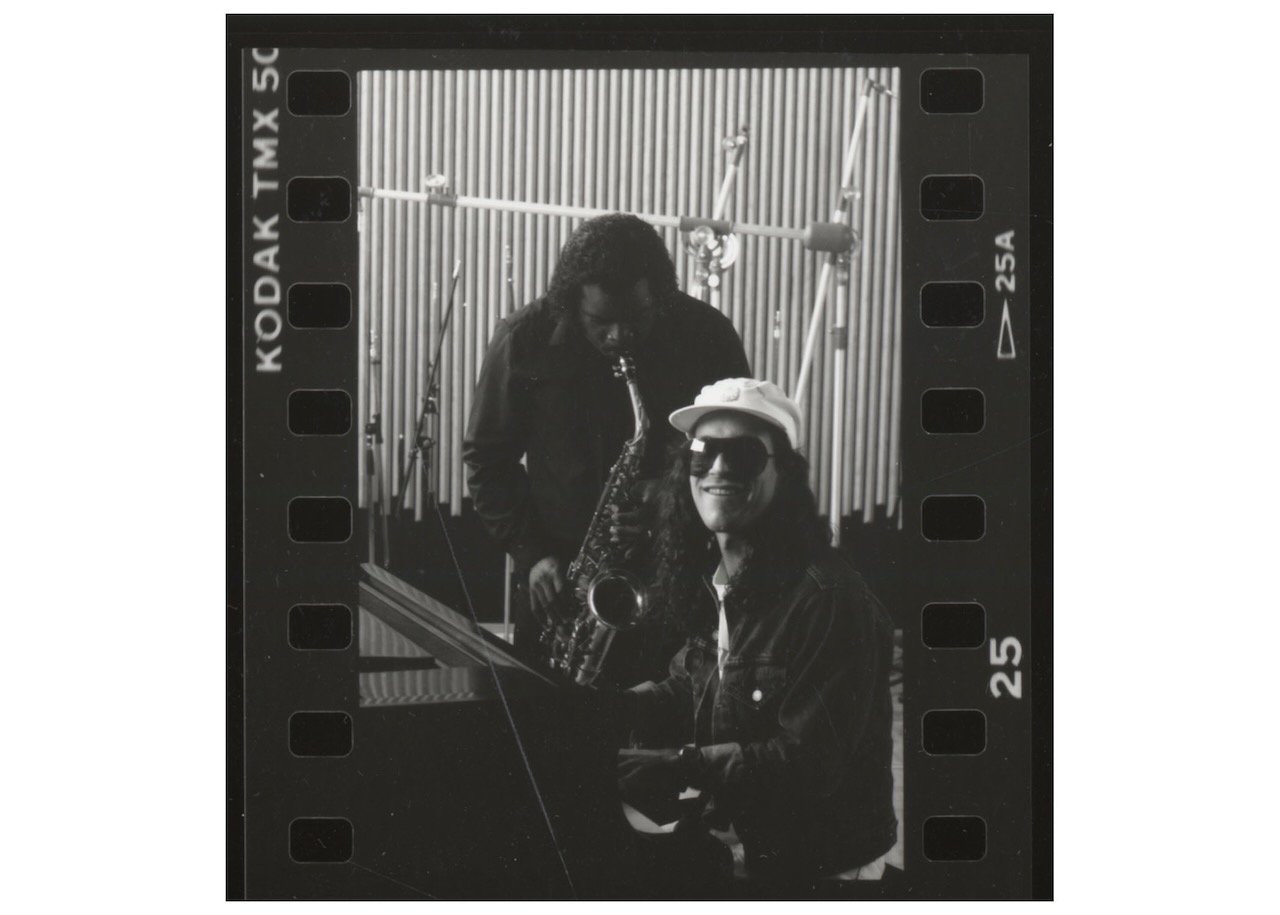

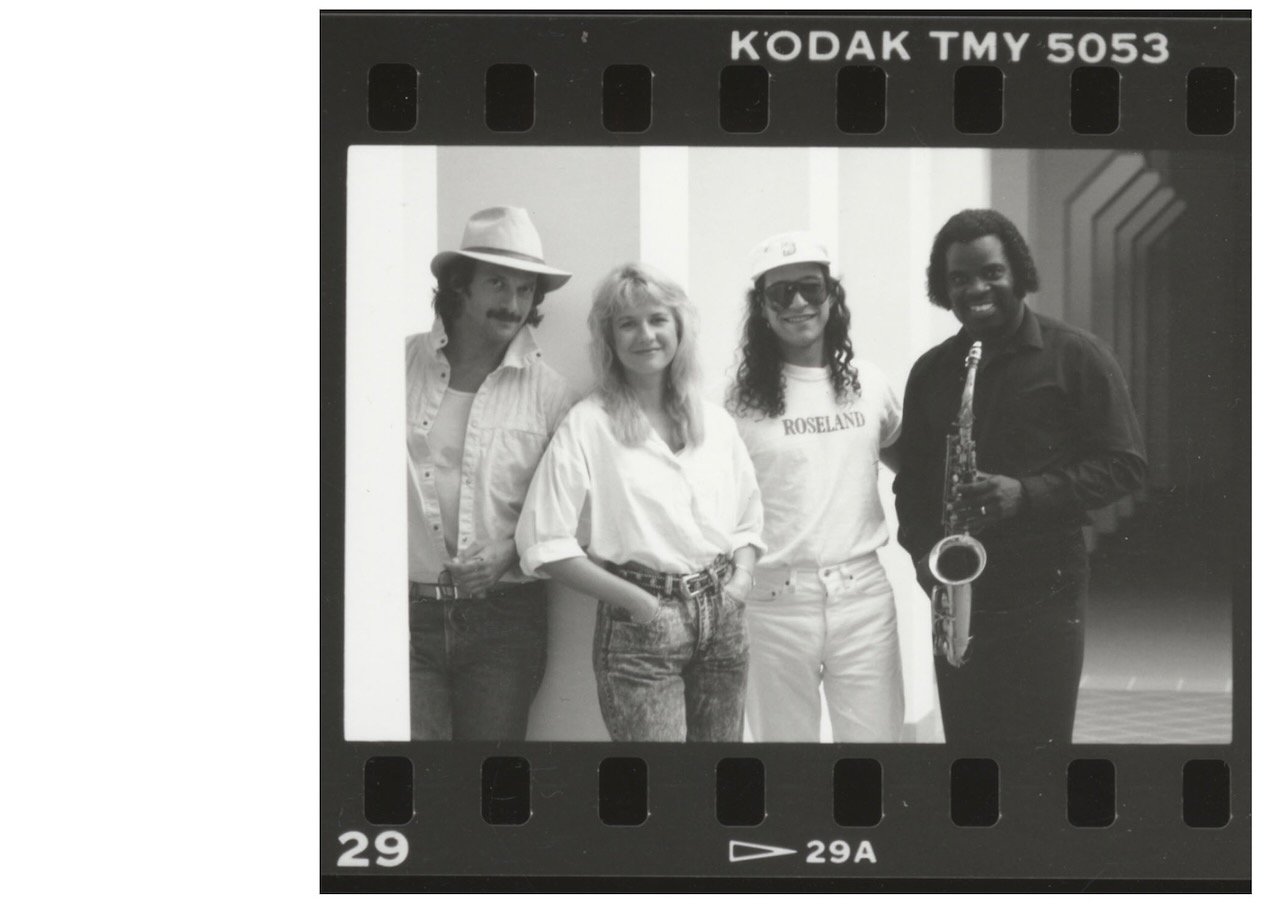

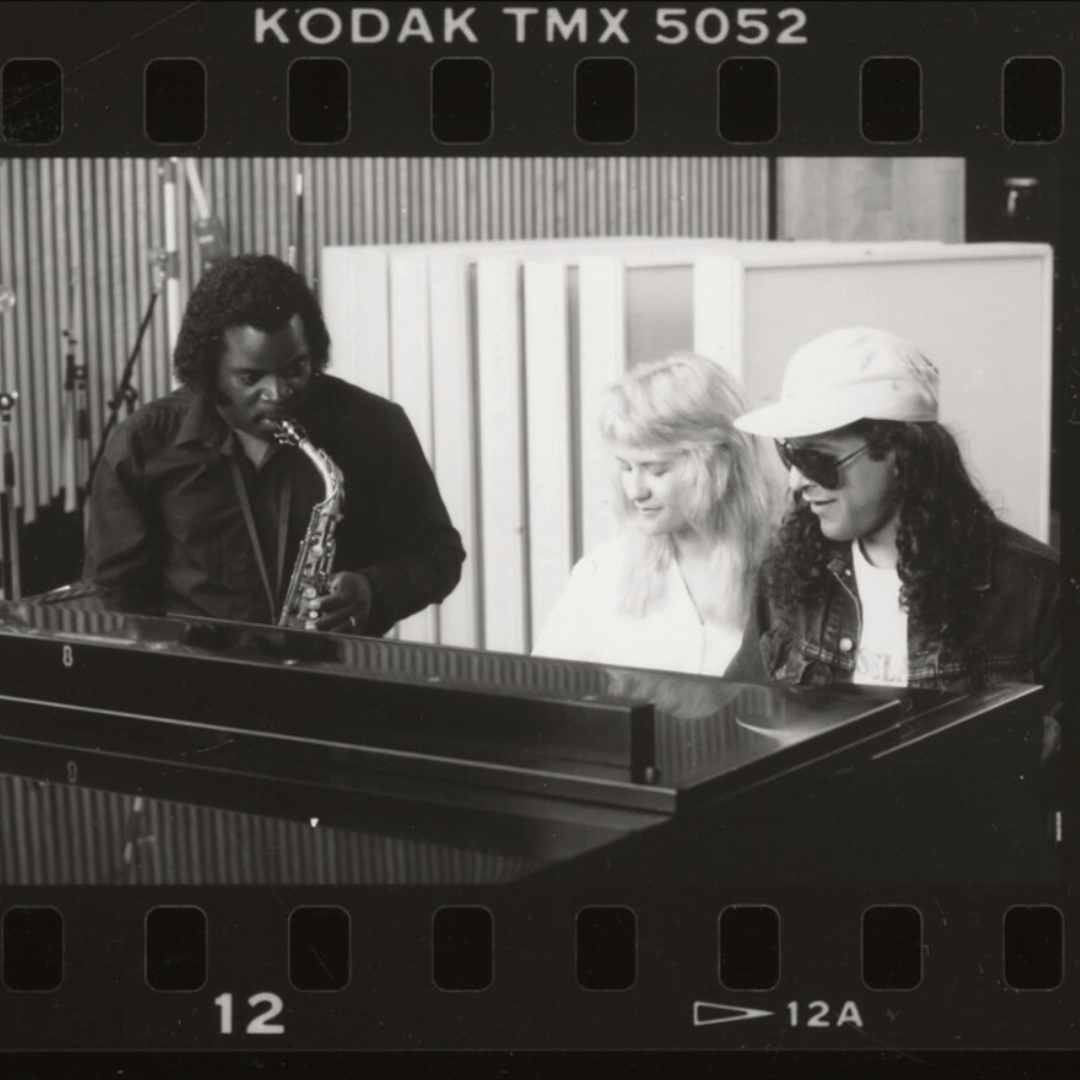

NU SHOOZ TIME MACHINE: Recording at Prince's Paisley Park

It’s Nu Shooz Time Machine Story #3! This one takes us to Paisley Park to record our second album, Told U So. Will John fit into Prince’s fur coat? Continue reading to find out more!

A while ago we asked the question, What would you like to see on our website?

The universal answer was (of course,) more stories about the ‘good old days.’ Some stories we’ve told over and over, like writing ‘Should I Say Yes’ in a full-blown [pun intended] tornado.

Is there anything left to say?

Valerie and I sat down and brainstormed, and came up with a pretty good list. We’ll take them in the order that they occurred to us. Here’s story #3.

Paisley Park, MN

The most futuristic building in Eden Prairie, Minnesota is Paisley Park, the home studio of Prince Rogers Nelson. Home studio is a little misleading. It’s a sprawling complex with three world-class recording rooms, a kitchen, and a full wardrobe department where they ‘built’ all his wild clothes.

We were there working on our second Atlantic record, Told U So. The producer was David ‘Z’ Rivkin.

We had the whole place to ourself for two weeks.

Our manager, Rick, asked me, “If you could have any guest stars on the record, who would it be?”

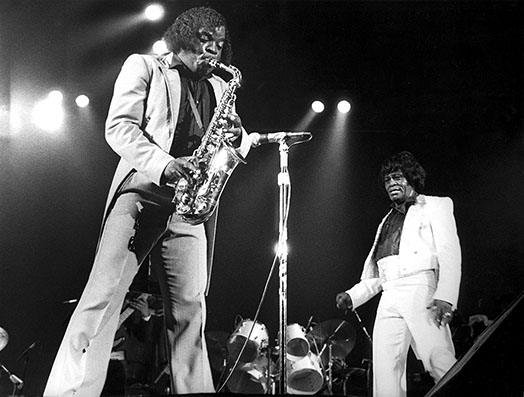

“Maceo Parker.”

Maceo was the alto saxophone player on all those late-60s James Brown records. He was one of my Soul Music heroes since I was eleven!

Rick found him somehow, and we flew him up to Minnesota. He played on our record for five hundred bucks. Said he could use the money ‘cause he had a half-dozen kids and lots of alimony payments.

James Brown used to name-check the kid

on his records.

That name-check made him famous.

David Z.

Maceo!

Blow your horn

Don’t want no trash

Play me some POPCORN

Maceo, C’MON!

When J.B. and the band got to Africa, the locals thought Maceo! was just a cool American thing to say, like hang ten or cowabunga!

So, I’m sitting behind the mixing board. Maceo starts playing on the title cut, and it sounds too…happy.

I look over at Rick. “This is Maceo Parker! How can I tell him what to play?”

“Go on,” Rick says. “You gotta do it.”

OK, so…

“Maceo…um…that’s a little too sweet. We’re looking for something a little more like…” I sing him his solo from Ain’t It Funky Now. [1969]

Bedop bedop vol-u-vop!

“Oh, ha HA!” He says. “You want that jagged stuff.”

Prince’s saxophone guy, Eric Leeds, shows up. He’s a great modern funky bebop player; perfect for Prince’s band. Plays mostly Bari. I tell him he’s one of my favorite horn players. He looks at me like dirt under his fingernails and says nothing.

Parker and Leeds are sitting in the corner. Maceo’s taking swigs off a bottle of blue mouthwash he carries around with him. He doesn’t drink, and he declines our invitation to dinner.

During the mixing, which was Rick’s job and bored me to death, I got to roam the studio. One room was full of every keyboard in the world. Another room was packed floor-to-ceiling with tapes. There was a guitar case in the hallway with a label that said, #3 PEACH.

I sat on the floor and took it out of the case. It was one of those wild Prince guitars, with the long protruding slightly suggestive upper horn.

The neck was skinny.

The action was tight.

John L. Nelson

Around this time, Prince’s father strolls in.

He’s a little old bald man in a purple suit, about the same height as ‘The Artist’ himself. He asks the receptionist for a few posters, “for his girlfriends.”

Prince was having a little pop-up concert at a club near the studio. David Z got us in. We got right up front. The band didn’t go on till two or three. Sheila Escovedo, (Sheila E) was the drummer. Damn, she was good! In musician speak, they dug a deep trench! We stood five feet from the man himself. They played non-stop for two and a half hours!

Sheila E.

Back at the studio the next day, I had more time to explore. Made my way up to the second floor, where the wardrobe department was. There were a dozen sewing machines at individual stations, like a factory.

In the corner, there were all these clothes. Famous clothes! There was the fur coat and wide-brimmed hat from the MTV Video for I-forget-what-song.

So, I’m there in the wardrobe room at Paisley Park.

Trying on Prince’s clothes.

They were so tiny.

Like clothes tailored for Tinkerbell,

Or Peter Pan.

NU SHOOZ Time Machine: Hangin' w/Alice Cooper

John runs into Alice Cooper at Atlantic Recording Studios in the 80s and learns a few production tricks in the process.

A while ago we asked the question, What would you like to see on our website?

The universal answer was (of course,) more stories about the ‘good old days.’ Some stories we’ve told over and over, like writing ‘Should I Say Yes’ in a full-blown [pun intended] tornado.

Is there anything left to say?

Valerie and I sat down and brainstormed, and came up with a pretty good list. We’ll take them in the order that they occurred to us. Here’s story #2.

Hangin’ With Alice Cooper 1986

Valerie and Rick, our manager, flew to D.C. to do some ‘Track Dates.’

A track date is where the singer appears at a dance club (like Larry Levan’s famous Paradise Garage above) to sing their hit over a backing track, usually around two or three in the morning.

We needed money to keep our nine-piece band alive, and Valerie could make more money doing one track date than the band could make in a week.

They left me in New York to mix some demo tapes. We had time booked at the legendary Atlantic Studios on 58th and 8th. Everybody recorded there back in the Golden Age; Ray Charles, Ruth Brown, Sinatra, Count Basie. You name it.

I didn’t really know what I was doing there. We had a stack of two-inch reels. We put them up, and a couple apathetic engineers fooled with them. I fell asleep on the couch, then got up and took a look around.

Down the hall, I ran into Arif Mardin, one of my producer heroes. He produced my favorite Chaka Khan album, What You Gonna Do For Me. But he also wrote up the horns for that first blast of Aretha Franklin singles, Respect, Think, and Chain of Fools.

And he knew about Nu Shooz!

“Nice horn charts,” he said.

I think I died and went to Heaven.

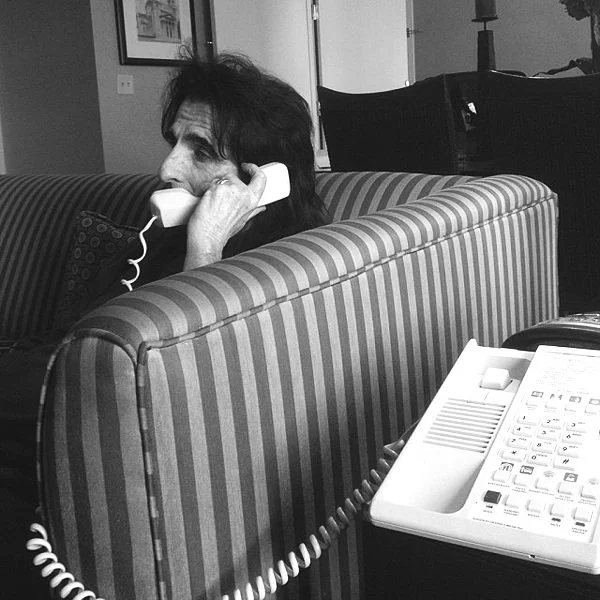

The second day, I come up the stairs and sitting at the receptionist’s desk is Alice Cooper. He’s manning the phones. Mr. Cooper sticks out his hand and says, “Vince.”

We order a couple of hamburgers.

While we’re eating he talks about how much he loves golf. His accent is distinctly mid-western, though later he owned a sports bar in Phoenix.

He was making a new album in the studio next to where I was (supposed to be) working. I was welcomed in to watch his sessions. Learned a whole lot. He had some beefy weight-lifter dude overdubbing guitars on a B.C. Rich. Machine tracks, live guitar. The coolest part was that they put the live drummer on last. That’s when the whole record came alive. I took that lesson with me when I left New York.

What a great down-home guy was Vincent Damon Furnier.

Never saw him bite the head off a bat. He said he doesn’t really go in for that kind of thing.

Don't Push The River: Movement Is Life

Thirty million years ago, we were writing songs for the fifth Nu Shooz album. It was a struggle. The label hated everything we handed in. We began to doubt ourselves. But I’m proud to say we didn’t stop.

Movement is life, and by moving, we know we’re alive.

Sink or swim, baby.

The continuing saga of Kung Pao Kitchen.

The I-Ching says this:

"IT FURTHERS ONE TO CROSS THE GREAT WATER."

What does that mean?

It means that movement is life.

We try things. We succeed. We fail. And all our endeavors further us in some way.

Thirty million years ago we were writing songs for the fifth Nu Shooz album. It was a struggle. The label hated everything we handed in. We began to doubt ourselves. But I’m proud to say we didn’t stop.

Movement is life, and by moving, we know we’re alive.

Sink or swim, baby.

Sometimes the river fights back. Strong currents want to drown us. If we struggle, we only get tired. (There’s truth in the metaphor I’m beating to death here.)

We worked hard on the songs. I suppose I could use something about rowing against the current. In the end, the label decided to shelve the record.

So now it’s now.

We dusted off the tapes and hey, they’re pretty cool. We spent the next four months scraping them into little sandcastles, adding stuff, taking stuff out. It’s obsessive work…fun work.

"The album will be done in five more days!" Then…Blamp!

The computer is dead.

This is not just a computer. It’s a Mac Pro with a Pro-Tools HDIII system running the new Version 9 software. Only guys with really thick glasses know how to make this thing go.

"Don’t worry, no data was lost."

While this is going on, we received news that a key member of the band was diagnosed with cancer.

This put everything in a different light. Sometimes it feels ridiculous to work on music in the face of grim reality. And then...sometimes it feels like the only thing left to do.

Keep on moving.

The computer is running again.

The cancer has been stared directly in the eye. The Doctor said, “You’ll have to find something else to die of.”

Yesterday we opened up the recovered Kung Pao Kitchen tracks and listened to them. Valerie said she thought horns would be good on one of the songs. After she said that, other songs sprouted horns. It’s like the whole record went from three dimensions to four! Nothing was lost.

While we were busy fighting the tides, they were changing us, and changing the landscape around us. The roiling waters changed us in ways we couldn’t guess.

It’s going to be a great record, a different record.

We try things. We succeed. We fail.

And all our endeavors further us in some way.

Movement is life.

- JRS

9/1/11

![Welcome to your summer. Yes, it's finally here! And it's the 46th anniversary of the very first NuShooz gig. [Colonel Summer's Park, Portland, Oregon, June 21st, 1979.] What a different world that was; pre-internet, no smartphones or smart toasters,](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54cee645e4b01fa0f0bfc5f9/1750512289030-8M6PFU9H9F6KHZ2HFJ94/image-asset.jpeg)